Last week, I was the final speaker in our department’s grad student association speaker series (which also marked the last day of classes for AY 2015-2016, hooray!), called “Rough Cut” – designed to expose current grad students to research-in-progress. I had signed up much earlier in the semester, and as the date drew closer, I wondered: did the grad students really want to hear about my interventions into PRC history and the cultural history of 20th c. China? Sure, listening to how fully (or semi-fully) fledged scholars are working through projects-in-process is useful – but most of me was saying ‘This has very little overlap with what most of our grad students do, and they will listen politely and ultimately leave not having learned a whole hell of a lot of useful stuff.’ They’re a very nice bunch, but subjecting people I like to 20 or 30 minutes of talk on something they have little background in seemed … selfish, to say the least. So I decided to do something a little different – instead of talking through the intricacies of my research in process, I’d walk them through how I got from a 2nd year research paper, to a dissertation, to a manuscript in progress. At the very least, I might be able to drop a few pieces of advice that might prove useful – even to people doing work that’s radically different than mine, in area and in emphasis. It was quite possibly just as useless as talking about my research, and only my research; but the intent was, at the very least, to be a bit broader and more useful.

Last week, I was the final speaker in our department’s grad student association speaker series (which also marked the last day of classes for AY 2015-2016, hooray!), called “Rough Cut” – designed to expose current grad students to research-in-progress. I had signed up much earlier in the semester, and as the date drew closer, I wondered: did the grad students really want to hear about my interventions into PRC history and the cultural history of 20th c. China? Sure, listening to how fully (or semi-fully) fledged scholars are working through projects-in-process is useful – but most of me was saying ‘This has very little overlap with what most of our grad students do, and they will listen politely and ultimately leave not having learned a whole hell of a lot of useful stuff.’ They’re a very nice bunch, but subjecting people I like to 20 or 30 minutes of talk on something they have little background in seemed … selfish, to say the least. So I decided to do something a little different – instead of talking through the intricacies of my research in process, I’d walk them through how I got from a 2nd year research paper, to a dissertation, to a manuscript in progress. At the very least, I might be able to drop a few pieces of advice that might prove useful – even to people doing work that’s radically different than mine, in area and in emphasis. It was quite possibly just as useless as talking about my research, and only my research; but the intent was, at the very least, to be a bit broader and more useful.

It went OK. Luckily, I was the only speaker on the agenda, because I blathered on for 40 minutes (the ‘ideal’ time was 15 or 20 – I’m usually much better at reining myself in, although I did know I’d be the only speaker). While chewing my nails and worrying at a colleague afterwards, she said: ‘You managed to sum up your entire grad career in 40 minutes, which is pretty good!’ I did gallop through quite a lot, both in terms of explaining my own research and (the more important bit) talking about process and what I wish I’d known when I started writing a dissertation.

Preparing the talk provided a nice bit of reflection and perspective, which I badly needed at the end of a semester (academic year, at that) that left me feeling pretty demoralized and defeated. I’ve been in pretty bad headspace since last fall & have been making concerted efforts to get myself out (not the easiest thing, but I’m glad some healthy habits are starting to stick!), and it’s easy to get trapped in those negative feelings. So throwing together a PowerPoint on my grad school career helped refocus me on my mss (and this is the ‘Summer of the Book,’ since the mss needs to be done & ready to go out by August), and think about all the good stuff I’ve done since I got to grad school in 2007.

In any case, amongst all the other stuff I talked about – the need to be strategic, the need to think about how you’ll sell your project to scholars in a variety of fields, the necessity of getting critical (and sometimes painful) feedback – I talked about having talismans for your work. Things you can brush up against while in the thick of things, that have meaning for you, but not necessarily for the work as a whole. This may not be a necessity for many people, but it’s necessary for me. My talismans, as I explained to the seminar room, are literary: I showed them the epigraphs from my dissertation, which include a line about archives from a not-terribly-distinguished book on the murder of the Russian imperial family in 1918, a line from the terribly distinguished Lantingjixu by Wang Xizhi, and a good clip of T.S. Eliot’s “Burnt Norton” from Four Quartets (I’ve written a bit about the latter – well, hell, the other two, as well – at various points in this blog). I don’t think talismans need to be literary, but mine are – they help me recenter myself when I’m lost in the chaos of research, writing, and editing.

I ended the whole presentation with another, newer talisman – one of the most famous quotes from Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, “Manuscripts don’t burn.” At the end of my first year at MSU, a colleague recommended the novel to me – I’d never read it, and in truth, have shied away from fiction for years (that goes for films, too). Documentaries, non-fiction, non-Chinese-history-monographs and the like, fine – I have consumed a lot of those since I started grad school, but my affection for fiction had really waned. The Master and Margarita was one of the first novels I’d read in years, and I loved it. Part of it was the description of life in the Soviet socialist literary system: the first few chapters were so on point! I recognized all of it. I remember sending an email at 3 AM – having been up a good chunk of the evening and wee hours reading – to the colleague who had recommended it, saying how fabulous it was. The rest of the novel was just magical, and absurd, and utterly wonderful. I recently passed it off to a friend who just finished her dissertation a few weeks ago – she said she was overwhelmed with choices of novels to read now that she had time, and so I handed over my copy of Bulgakov’s masterpiece.

I ended the whole presentation with another, newer talisman – one of the most famous quotes from Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, “Manuscripts don’t burn.” At the end of my first year at MSU, a colleague recommended the novel to me – I’d never read it, and in truth, have shied away from fiction for years (that goes for films, too). Documentaries, non-fiction, non-Chinese-history-monographs and the like, fine – I have consumed a lot of those since I started grad school, but my affection for fiction had really waned. The Master and Margarita was one of the first novels I’d read in years, and I loved it. Part of it was the description of life in the Soviet socialist literary system: the first few chapters were so on point! I recognized all of it. I remember sending an email at 3 AM – having been up a good chunk of the evening and wee hours reading – to the colleague who had recommended it, saying how fabulous it was. The rest of the novel was just magical, and absurd, and utterly wonderful. I recently passed it off to a friend who just finished her dissertation a few weeks ago – she said she was overwhelmed with choices of novels to read now that she had time, and so I handed over my copy of Bulgakov’s masterpiece.

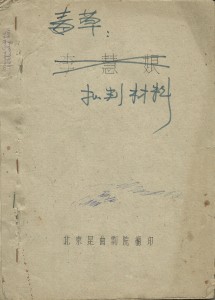

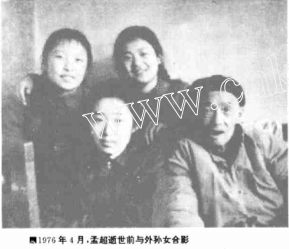

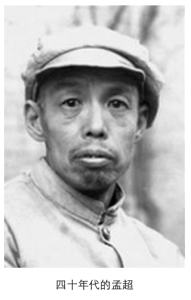

In any case, since “Manuscripts don’t burn” is such a famous line, it feels trite to pick it as a talisman, and yet – it’s oh-so-appropriate. I use it to remind myself that as much as I love my wonderful intellectuals, they wrote and said and did things that (whether I agree with it or not) ran afoul of powerful elements of the CCP. Those “manuscripts” don’t burn. I owe it to them to tell their stories, warts and all; you can’t expunge the flip side of the ‘brave intellectuals standing up in the face of Mao’s vision run amok,’ which is, ‘Oh my god, what were they thinking, criticizing the ’emperor.” Often when I’m writing through the 1960s, I find myself cringing as one does when watching a horror film: ‘Oh no, don’t do that, don’t say that, oh god.’ Obviously I come down on one side of that particular history, but their story is more compelling by the fact that they must have known what they were saying and doing. To render Meng Chao’s ultimate fate evidence of nothing more than the capriciousness of Mao et al. is ultimately, I think, a disservice to someone who wrote and published (in multiple versions!) lines like:

My worry is for the bitterness of refugees of disasters,

My worry is for the resentment of those forced to wander.

The lakeside scene glitters,

But the howling of the people of Lin’an is more desperate than the howling of ghosts.

Under the hand of Jia Sidao,

Even after death, it’s difficult to find peace!

Even if we’re going to play the whole ‘Oh, they were talking about the prime minister, not the emperor, ergo weren’t talking about Mao himself!’ game, putting into public writing (and performance!) – even just a few lines – worrying about starving people who are in desperate situations while government officials take pleasure in partying at West Lake is pretty provocative in the early 1960s, during and after the disaster of the Great Leap Forward & resulting famine.

So that manuscript doesn’t burn. None of them do. That’s not a bad thing.

However, I didn’t end my talk on that morose note; I ended it on a slightly more upbeat, worthy-of-a-bad-motivational-poster, yet still melancholy note. Our manuscripts don’t burn, and that’s also not a bad thing. It’s worth reflecting on failures, and remembering that every misstep along the way to a journal article, dissertation, or mss (or job entirely out of the academy) has something to offer. I have spent so much time writing things that wound up shuffled into a file somewhere; so much time reading sources that didn’t pan out (bad enough in English; triply painful in Chinese, at least for me); so much time roughing out projects that don’t pan out as you anticipate. Time spent building courses that don’t work. Time picking out readings that don’t work for courses that kinda do. Etc. etc. etc ….

Every academic career is, in some measure, a history of failure. Some more so than others – often, as has been frequently discussed, due to nothing other than the vagaries of the market. But a Princeton professor’s recent “CV of failures” made some traction on my lists in various places, and it is potentially useful to meditate on, I think (of course, as a follow-up oped in the same paper pointed out, “Only successful people can afford failures” – which is also true, and deserves as much rumination. It’s a lot easier to publicize your failures when safely ensconced in a tenure-track position (having come from a position of relative Privilege) at an elite university – or a non-elite one, for that matter). But ultimately, few people come out of the gate and have no stumbles, in any career. As much as I feel like a bad motivational poster for saying so, I have learned a lot from my failures, big and little. I have been blessed in my career since starting grad school, but I’ve fallen flat on my face plenty. The successes I’ve had have generally felt like completely bizarre, totally unexpected bright spots in the midst of disaster. And that’s not just my anxiety speaking: there were several times when senior people expressed some measure of surprise of ‘Oh, that worked out for you!’ at critical points in my career.

But. Manuscripts don’t burn. The history of my career doesn’t burn, the mistakes I made haven’t, and ultimately – while I don’t think they’ve made me the historian I am, they made me the Chinese historian I am.

It’s finals week, so I’ve been catching up on grading, getting a lot of work done, and also tried to wind down from a  stressful year by watching documentaries and other things that make me happy. There’s a wonderful line in the documentary Elusive Muse (the subject of which is Suzanne Farrell, the last great Balanchine muse – I’ve written about that a bit here, too), which I watched a few days ago while zoning out on the couch. The choreographer Maurice Béjart, who took Farrell and her husband in after they left the New York City Ballet, had this to say on why Farrell was one of the great dancers of the 20th century (and probably ever):

stressful year by watching documentaries and other things that make me happy. There’s a wonderful line in the documentary Elusive Muse (the subject of which is Suzanne Farrell, the last great Balanchine muse – I’ve written about that a bit here, too), which I watched a few days ago while zoning out on the couch. The choreographer Maurice Béjart, who took Farrell and her husband in after they left the New York City Ballet, had this to say on why Farrell was one of the great dancers of the 20th century (and probably ever):

She was different … and she was even different from the Balanchine girls … she was completely different, and – I was very surprised – she had a freedom of movement, with a very clear technical power. But you never felt the technical, you felt the freedom and the musicality. I mean, she’s like – she’s like a violin, I mean, the music comes out from her body.

I’ve heard Béjart utter those lines – and they are memorable ones, I’ve quoted them (badly) to people at several points – any number of times, but something clicked for me in the past two weeks. I want to be technically skilled; but I don’t want people to see it necessarily, because I want to weave a great story. I want it to come out from my writing; I want to be an instrument of a sort – I want the story to come out, which relies on the technical power, while rendering that relatively invisible.

Talismans: they’re important, no matter what you do. And … manuscripts don’t burn. Farrell was great partially because she simply – after a point – wasn’t afraid of making mistakes, which made her highest highs (which were supreme!) possible. A useful lesson, hard as it is to remember when tenure and the judgment of various people (the vast majority of whom aren’t in your field & want to know what you’re not doing XYZ to contribute in ABC ways) are breathing down your neck.

In any case, coming off a semester that was a bit of a downer from multiple angles, I’m eager and ready to get back to the classroom. I am teaching one of my perennial favorites – Gender in Asia (pre-modern edition!) – and am so excited to be teaching with some of my very favorite things: the KagerÅ nikki, my beloved, battered Chinese women writer’s anthology (dog eared and marked up, a purchase I made in Taiwan before I even started grad school – for the then-princely sum of 1225NT, around $35), Chunhyang, Sei ShÅnagon, Susan Mann and Dorothy Ko’s scholarship …

In any case, coming off a semester that was a bit of a downer from multiple angles, I’m eager and ready to get back to the classroom. I am teaching one of my perennial favorites – Gender in Asia (pre-modern edition!) – and am so excited to be teaching with some of my very favorite things: the KagerÅ nikki, my beloved, battered Chinese women writer’s anthology (dog eared and marked up, a purchase I made in Taiwan before I even started grad school – for the then-princely sum of 1225NT, around $35), Chunhyang, Sei ShÅnagon, Susan Mann and Dorothy Ko’s scholarship … In any case, I am really really really really really excited about this class (really. Really!). We have a whole whack of cool things to read, from classic narratives of first ascents and Western derring-do in exotic locales, to fascinating academic work like Sherry Ortner’s Life and Death on Mt. Everest. And a whole bunch of other things besides – Daphne du Maurier’s haunting novella “Monte Verità ,” news articles, academic articles on … eating and shitting on Mt. Everest? But one of the most novel things about the course is that – for once – I actually have the opportunity to really blend my research and teaching lives.

In any case, I am really really really really really excited about this class (really. Really!). We have a whole whack of cool things to read, from classic narratives of first ascents and Western derring-do in exotic locales, to fascinating academic work like Sherry Ortner’s Life and Death on Mt. Everest. And a whole bunch of other things besides – Daphne du Maurier’s haunting novella “Monte Verità ,” news articles, academic articles on … eating and shitting on Mt. Everest? But one of the most novel things about the course is that – for once – I actually have the opportunity to really blend my research and teaching lives.

I have a whole whack of backlogged posts-to-write that I haven’t gotten around to: the end of spring semester (the end of my second year as a full-fledged assistant professor!) was full and busy. Two conferences, including a trip to Canada, thoughts on teaching an experimental-for-me course, other assorted bits of my life. Frankly, as summer slides by – as it’s wont to do when you’re an academic, I was at the dentist a few weeks ago & the hygienist said to me ‘It must be so nice to have the whole summer off!’, and I could only laugh, because it’s not quite that simple – every day means it’s less likely for me to go back and write those posts, or finish the half-written ones in my queue. I may sit on quiet, cool nights and tap through my phone, looking at photographs and little snippets of video that make me smile, but I don’t really want to write about them. But a past of mine that passed into history long ago: well, that’s a little easier to write about. A little more like writing proper history.

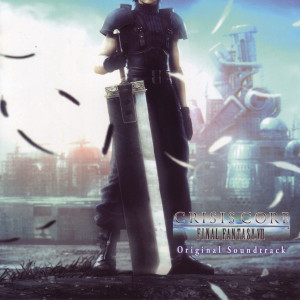

I have a whole whack of backlogged posts-to-write that I haven’t gotten around to: the end of spring semester (the end of my second year as a full-fledged assistant professor!) was full and busy. Two conferences, including a trip to Canada, thoughts on teaching an experimental-for-me course, other assorted bits of my life. Frankly, as summer slides by – as it’s wont to do when you’re an academic, I was at the dentist a few weeks ago & the hygienist said to me ‘It must be so nice to have the whole summer off!’, and I could only laugh, because it’s not quite that simple – every day means it’s less likely for me to go back and write those posts, or finish the half-written ones in my queue. I may sit on quiet, cool nights and tap through my phone, looking at photographs and little snippets of video that make me smile, but I don’t really want to write about them. But a past of mine that passed into history long ago: well, that’s a little easier to write about. A little more like writing proper history. The game related to 7 that was mine was a PSP spinoff released in 2008, Crisis Core. It’s a beautiful little game in a lot of ways. I got it not because I was so attached to 7, but because I had played 7 & was curious about how Square was going to deal with a game where you knew the outcome before you started playing. I had also lived in Taiwan between 2006 & 2007, when FFVII prequel mania was at its height – my terrible little bathroom in my terrible (but wonderful) little rooftop one room studio with no kitchen had a FFVII prequel wall hanging in it (bathroom not shown here, but you get the idea). Crisis Core is a game where the main character is one that you know is dead in 7, the game that comes after. How does a writer deal with that? Can you write a satisfying story where everyone – well, everyone that had played the main game, which is the target audience here – playing it knows the character you’re playing is going to die? They did. I cried at the end – an end I knew I was coming. Maybe that’s why I liked it: it was like writing history with a sad end, where you know things are going to end badly.

The game related to 7 that was mine was a PSP spinoff released in 2008, Crisis Core. It’s a beautiful little game in a lot of ways. I got it not because I was so attached to 7, but because I had played 7 & was curious about how Square was going to deal with a game where you knew the outcome before you started playing. I had also lived in Taiwan between 2006 & 2007, when FFVII prequel mania was at its height – my terrible little bathroom in my terrible (but wonderful) little rooftop one room studio with no kitchen had a FFVII prequel wall hanging in it (bathroom not shown here, but you get the idea). Crisis Core is a game where the main character is one that you know is dead in 7, the game that comes after. How does a writer deal with that? Can you write a satisfying story where everyone – well, everyone that had played the main game, which is the target audience here – playing it knows the character you’re playing is going to die? They did. I cried at the end – an end I knew I was coming. Maybe that’s why I liked it: it was like writing history with a sad end, where you know things are going to end badly. I played it on a PSP that I had bought myself on a whim the Christmas of ’07, at the end of my first quarter of grad school: I remember getting on the highway & driving down to the area with all the big box stores so I could go to GameStop. I came home with a trusty black PSP, which remained trusty and well-traveled until it was replaced with a Vita this year, long after it had become obsolete. It lives in my basement still, in its nice case, the kind that you could insert your own image into – which I carefully trimmed a photograph of the Meiji Temple in winter to fit, from my beautiful Christmas cards I used while I was in coursework. The interior simply said Peace. I still have a few in a desk drawer in my home office; I couldn’t bring myself to use all of them. I tried to find a case like that for my DS or Vita, because I just wanted to carry that beautiful image again, and I came up empty. That case (and PSP) went all over the US & to China (and various points in between), and now lives in my basement, mostly forgotten.

I played it on a PSP that I had bought myself on a whim the Christmas of ’07, at the end of my first quarter of grad school: I remember getting on the highway & driving down to the area with all the big box stores so I could go to GameStop. I came home with a trusty black PSP, which remained trusty and well-traveled until it was replaced with a Vita this year, long after it had become obsolete. It lives in my basement still, in its nice case, the kind that you could insert your own image into – which I carefully trimmed a photograph of the Meiji Temple in winter to fit, from my beautiful Christmas cards I used while I was in coursework. The interior simply said Peace. I still have a few in a desk drawer in my home office; I couldn’t bring myself to use all of them. I tried to find a case like that for my DS or Vita, because I just wanted to carry that beautiful image again, and I came up empty. That case (and PSP) went all over the US & to China (and various points in between), and now lives in my basement, mostly forgotten. I haven’t read it in years. But I remember saving a tab in my browser after it was published (where? I don’t even remember – maybe it was just on her Sexyvideogameland blog, the one that I linked to over and over when I wrote for Kotaku), and going back to look and look again, like I always do with good writing. In it, she talked about playing this game, this prequel to a game that had meant so much to her, and playing it while in the midsts of a relationship that was breaking down. And it wasn’t just that she was playing through this game where you know the main character is going to die, where the designers are deliberately making your heart stop with all these echoes of the game before, the game you are so attached to. But that original game formed the basis of that relationship that was breaking down. She wrote of this dying relationship, and silently passing the PSP between them, looking at this end-beginning – whatever one would term a prequel – that you know is going to end badly, at least for the current incarnation. And you have something here, in the right now, that is ending badly. But it’s a start, too: something new. It isn’t just the past replaying itself again and again.

I haven’t read it in years. But I remember saving a tab in my browser after it was published (where? I don’t even remember – maybe it was just on her Sexyvideogameland blog, the one that I linked to over and over when I wrote for Kotaku), and going back to look and look again, like I always do with good writing. In it, she talked about playing this game, this prequel to a game that had meant so much to her, and playing it while in the midsts of a relationship that was breaking down. And it wasn’t just that she was playing through this game where you know the main character is going to die, where the designers are deliberately making your heart stop with all these echoes of the game before, the game you are so attached to. But that original game formed the basis of that relationship that was breaking down. She wrote of this dying relationship, and silently passing the PSP between them, looking at this end-beginning – whatever one would term a prequel – that you know is going to end badly, at least for the current incarnation. And you have something here, in the right now, that is ending badly. But it’s a start, too: something new. It isn’t just the past replaying itself again and again.

actually happen – another star serves as the “bridge”). This has, as far as I know, turned into some bizarre Valentine’s Day spin-off (at least partially), but originally, it was a celebration of women’s work (one of its alternate names is the Qiqiaojie 乞巧节, the ‘Begging for Skills Festival,’ referencing domestic skills & the practice of qiqiao 乞巧, making offerings to the Weaving Girl and holding competitions related to domestic tasks, like threading needles only by the light of the moon) & also one hoping for love or celebrating bonds. Or for missing lovers who were absent – not uncommon, at least among the poetry-writing literati, when husbands were not infrequently off on far-flung bureaucratic assignments and the like. In any case, it’s always struck me as a good deal mopier than Valentine’s Day, for the coupled and singled alike.

actually happen – another star serves as the “bridge”). This has, as far as I know, turned into some bizarre Valentine’s Day spin-off (at least partially), but originally, it was a celebration of women’s work (one of its alternate names is the Qiqiaojie 乞巧节, the ‘Begging for Skills Festival,’ referencing domestic skills & the practice of qiqiao 乞巧, making offerings to the Weaving Girl and holding competitions related to domestic tasks, like threading needles only by the light of the moon) & also one hoping for love or celebrating bonds. Or for missing lovers who were absent – not uncommon, at least among the poetry-writing literati, when husbands were not infrequently off on far-flung bureaucratic assignments and the like. In any case, it’s always struck me as a good deal mopier than Valentine’s Day, for the coupled and singled alike.

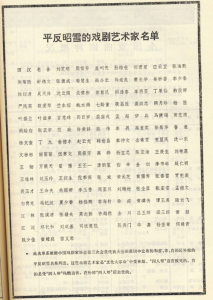

When I started looking more seriously at older parts of the historiography, I realized the field had spent some time sorting many of these people into various categories. “Establishment” intellectuals, for instance, or “revolutionary” intellectuals. These divisions can be useful, to a point; but they can also obscure a larger point, which is there was frequently a lot more similarities between these people than sorting them into different “camps” would lead you to believe. I don’t mean to imply I think there weren’t differences, or that seemingly minor differences don’t have an impact. As the political trials and travails of the 1950s and early 1960s – never mind the Cultural Revolution – indicate, there were camps, and your opinion on certain matters could have deadly consequences. But at the same time, from a distance of 70 years, there are a lot more similarities than differences. All of the people in my 1951 debate, for instance, agreed that China’s traditional culture was important and should be preserved. They disagreed on what that preservation should look like (among other things). But they agreed on one of the most important things of all: that this was worth arguing about, fighting over.

When I started looking more seriously at older parts of the historiography, I realized the field had spent some time sorting many of these people into various categories. “Establishment” intellectuals, for instance, or “revolutionary” intellectuals. These divisions can be useful, to a point; but they can also obscure a larger point, which is there was frequently a lot more similarities between these people than sorting them into different “camps” would lead you to believe. I don’t mean to imply I think there weren’t differences, or that seemingly minor differences don’t have an impact. As the political trials and travails of the 1950s and early 1960s – never mind the Cultural Revolution – indicate, there were camps, and your opinion on certain matters could have deadly consequences. But at the same time, from a distance of 70 years, there are a lot more similarities than differences. All of the people in my 1951 debate, for instance, agreed that China’s traditional culture was important and should be preserved. They disagreed on what that preservation should look like (among other things). But they agreed on one of the most important things of all: that this was worth arguing about, fighting over.

One of the most important commandments as a historian is “Do no violence to your sources”; treat them carefully, analyze them thoughtfully, be aware of what you are bringing to your interpretation. It seems that much more important when dealing with a life, especially a life that has been so little looked at in comparison to his peers. Knitting together these disparate pieces of a literary life makes me nervous, and I wonder sometime if I’m too likely to sympathize with men like Meng Chao (after all, Li Huiniang or not, he was part of The System that took root; surely he – and his compatriots – shoulder some of the burden for the disasters that came later, even if they themselves were swept up in them?). But he’s a very human actor to me, one that reminds me that all these other names and people (and scores of anonymous people besides) were people, and these were lives, and ultimately that’s the important part of the story – not abstract ideology or theory. One of my favorite pieces I ever wrote was for The Appendix, called

One of the most important commandments as a historian is “Do no violence to your sources”; treat them carefully, analyze them thoughtfully, be aware of what you are bringing to your interpretation. It seems that much more important when dealing with a life, especially a life that has been so little looked at in comparison to his peers. Knitting together these disparate pieces of a literary life makes me nervous, and I wonder sometime if I’m too likely to sympathize with men like Meng Chao (after all, Li Huiniang or not, he was part of The System that took root; surely he – and his compatriots – shoulder some of the burden for the disasters that came later, even if they themselves were swept up in them?). But he’s a very human actor to me, one that reminds me that all these other names and people (and scores of anonymous people besides) were people, and these were lives, and ultimately that’s the important part of the story – not abstract ideology or theory. One of my favorite pieces I ever wrote was for The Appendix, called

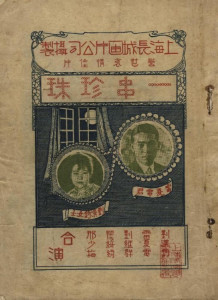

odds); it’s actually quite an important thing in Chinese literature, including some of the greatest things ever written in any language. The English translation doesn’t convey the cultural significance of roundness (as Zhang Zhen notes in An Amorous History of the Silver Screen: Shanghai Cinema, 1896-1937, the significance of datuanyuan goes way beyond a cliché, and points to a kind of cultural conditioning – she mentions, for instance, the importance of visual cues like the typical round table used for family meals, as well as cosmological symbols like the full moon, in early Chinese cinema that had a tendency to rely on the “big reunion” as a plot structure). Cultural resonance or not, forcing a datuanyuan sometimes leads to bizarre results, like in the 1926 film A String of Pearls (Yi chuan zhenzhu 一串çç ), based loosely (and I do mean “loosely”) on the famous Guy de Maupassant short story “La parure” (The necklace), where the emotional punch of the story is more or less removed by an effort to ensure the happy ending. I suppose this is one complaint with happy endings in games; they can seem contrived or leave massive plot holes.

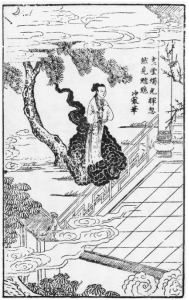

odds); it’s actually quite an important thing in Chinese literature, including some of the greatest things ever written in any language. The English translation doesn’t convey the cultural significance of roundness (as Zhang Zhen notes in An Amorous History of the Silver Screen: Shanghai Cinema, 1896-1937, the significance of datuanyuan goes way beyond a cliché, and points to a kind of cultural conditioning – she mentions, for instance, the importance of visual cues like the typical round table used for family meals, as well as cosmological symbols like the full moon, in early Chinese cinema that had a tendency to rely on the “big reunion” as a plot structure). Cultural resonance or not, forcing a datuanyuan sometimes leads to bizarre results, like in the 1926 film A String of Pearls (Yi chuan zhenzhu 一串çç ), based loosely (and I do mean “loosely”) on the famous Guy de Maupassant short story “La parure” (The necklace), where the emotional punch of the story is more or less removed by an effort to ensure the happy ending. I suppose this is one complaint with happy endings in games; they can seem contrived or leave massive plot holes. This is much harder to do in literature, for obvious reasons, although a single work can encompass all those moments. In drama, this is helped by the fact that the sprawling Ming tales were not performed in their entirety, and were instead seen in excerpts. Some of the most enduring parts of Tang Xianzu’s 汤显祖 masterwork The Peony Pavilion (Mudan ting 牡丹äº), or at least the ones that get trotted out the most, are not, in fact, the end, where everything works out – they are the beautiful and rather tragic (or at least bittersweet) early scenes. Considering the fears of moralists that chuanqi like Peony would drive women to madness, suicide, or worse, it seems that even having a happy ending was no guarantee your audience would gravitate towards that! Instead, portions of the reading audience seemed to fixate on the somewhat depressing (perhaps more realistic?) chapters – an acknowledgement that the datuanyuan was simply a fantasy, impossible in real life? The famous “Walking through the garden, waking from the dream” [Youyuan jingmeng 游å›æƒŠæ¢¦] section is rather wondrous – and it does feature quite the fantastic dream! – yet it’s simply that: a dream. And yet the (male) authors seemed to love writing the fantastical ending, no matter how improbable, even if those weren’t the parts segments of their audience gravitated towards. Perhaps this is partially a difference in producing and consuming; I wonder if fan-produced writing and art geared towards alternative paths or endings, fleshing out what happened after, writing a “perfect” scenario, whatever that might mean for an individual, often focuses more on the perhaps improbable yet perfect because it’s created largely to entertain one’s self and not really for an audience (publishing on fandom specific sites and the like notwithstanding) – not unlike some of the great fiction and drama in China.

This is much harder to do in literature, for obvious reasons, although a single work can encompass all those moments. In drama, this is helped by the fact that the sprawling Ming tales were not performed in their entirety, and were instead seen in excerpts. Some of the most enduring parts of Tang Xianzu’s 汤显祖 masterwork The Peony Pavilion (Mudan ting 牡丹äº), or at least the ones that get trotted out the most, are not, in fact, the end, where everything works out – they are the beautiful and rather tragic (or at least bittersweet) early scenes. Considering the fears of moralists that chuanqi like Peony would drive women to madness, suicide, or worse, it seems that even having a happy ending was no guarantee your audience would gravitate towards that! Instead, portions of the reading audience seemed to fixate on the somewhat depressing (perhaps more realistic?) chapters – an acknowledgement that the datuanyuan was simply a fantasy, impossible in real life? The famous “Walking through the garden, waking from the dream” [Youyuan jingmeng 游å›æƒŠæ¢¦] section is rather wondrous – and it does feature quite the fantastic dream! – yet it’s simply that: a dream. And yet the (male) authors seemed to love writing the fantastical ending, no matter how improbable, even if those weren’t the parts segments of their audience gravitated towards. Perhaps this is partially a difference in producing and consuming; I wonder if fan-produced writing and art geared towards alternative paths or endings, fleshing out what happened after, writing a “perfect” scenario, whatever that might mean for an individual, often focuses more on the perhaps improbable yet perfect because it’s created largely to entertain one’s self and not really for an audience (publishing on fandom specific sites and the like notwithstanding) – not unlike some of the great fiction and drama in China.