Some assorted musings that are far from complete, probably painting plenty of things with too broad a brush, and a bit kneejerk in reaction. Well, these things happen – it’s a start, and I’ll sort some of this out later.

What shade of blue is the sky?

A Killscreen piece has been making the rounds of late (“‘Game designers want to be artists without knowing what that means’“). I confess it rubbed me the wrong way for a lot of reasons, some that I haven’t quite put my finger on. It’s just … well. A little too simplistic, even for a simplistic laundry list of questions, I think.

Why do you think game designers are so misinformed [about what art is]?

I’m generalizing, but game developers are coming out of computer science or a different side of universities, if they’ve studied art at all. At most, they’ve had one or two art history classes and most of those are boring. People haven’t taken time to understand what it means to be an artist.

Let me say at the outset: I think it would be great if more people had more courses in things like art history, or history, or art, or literature, or foreign languages (multiples). I am a huge believer in the benefits of the ideal model of the liberal arts education (whether or not it’s attainable, feasible, or has existed for a long time is a debate for another day). But this isn’t about courses. What this is really about is being a culturally well-rounded person: crash courses and college courses can help, but they certainly don’t make up for simply living your life in such a way that you’re steeped in a variety of cultural things that you’re constantly thinking about. What department you’re in doesn’t have much to do with it. Plenty of people in the humanities are not exactly paragons of cultural beings. I am certain there are art historians who have no idea of “what it means to be an artist.”

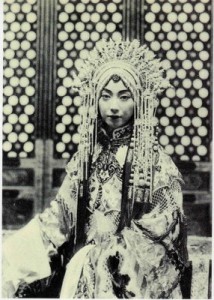

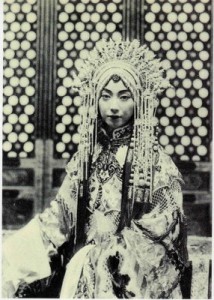

Mei Lanfang 梅兰芳

It’s not simply about “taking the time” to think about something; it requires energetic, sustained engagement. When I think of my development as a historian, it’s something that’s happened over a very long period of time, and much of it has simply happened in the course of living my life the way it wound up (Sharp points to this in a later comment – the process is ongoing). There was – is – no way to force it. The disciplinary example is a red herring. This isn’t about disciplines – the art historians who haven’t thought very much about “what it means to be an artist” probably haven’t done so because that’s not what it means to be an art historian in their corner of the Ivory Tower. It’s also like asking what shade of blue is the sky: there is no right answer. It’s such a broad question as to be meaningless. What kind of artist are we talking about? A dancer, a musician, a writer, a painter? Are we talking about a choreographer, a prima ballerina, or a member of the corps de ballet? A composer, a conductor, a pianist, a first chair flute, a second row trumpet? They’re all artists, after all – but it all means something very different. Besides, many art historians aren’t going to have any better idea how to approach many kinds of artists than I: it’s not an all-encompassing field, after all. Does Sharp have any idea “what it means” to be a Chinese opera star? They are artists, after all. Then again, does it really matter if he does – or doesn’t?

But I don’t want to poke petty little holes in an argument that I don’t particularly disagree with; I just think it’s framed in the wrong way. This isn’t about what computer science majors are or are not doing – it’s about what’s prized out there on the open market in a lot of ways.

Here’s what I’d like to consider: what kind of person is the industry selecting for? Are they selecting for people who are likely – regardless of background – to be culturally well-rounded, with plenty of examples and a broad worldview to draw on? The ones who have “thought about what it means to be an artist,” or any number of other things? What kinds of backgrounds are important?

Well, now that you mention it …

The “developers wanna be artists but have no clue what that means” article was sent my way by a friend who actually wanted to bring up a (related) issue – one that’s bound up with the background/breadth question. I will preface this with: I am not, nor have I ever been, a student of game design, an aspiring designer, an actual designer, or a computer science major. I’ve never taken a CS class and I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t be any good at it (luckily, I’ve never had to try!). I can’t code, couldn’t design a game for you if you held a gun to my head, and so on. Brenda Brathwaite gave a talk at GDC ’11 on how game design students need to have a coding background. Not just background, actually, their degrees should involve the “same level of coding as a comp science degree” (this statement is what my friend took umbrage with). “This sort of ignores all the other things that go into making a good game designer, no?” is a dumbed down version of my friend’s argument against such thinking – requiring comp sci levels of ability cuts out the people who can master the basics and acquire a good understanding, but aren’t ever going to be proficient in the way that a comp sci specialist will be. Which isn’t to say some people aren’t going to have that level of mastery, just that maybe it shouldn’t be an expectation?

I get the need for strong basics. Here’s an example from my own field: one of the tools of our trade, one of the most basic building blocks of our work, is language ability. It is critical to what we do: we must have a certain grasp on modern and classical Chinese, regardless of our eventual research subject, and we must pass tests demonstrating the standard of proficiency our advisors deem sufficient. However – and this is a big however – we are not expected to have the “same level of Chinese mastery as a Chinese literature major.” Some people assuredly do, many of us do not, and it funnels our research accordingly. I was told by a professor that they approached their dissertation topic from angle B because their linguistic abilities were insufficient for angle A. Said professor still turned out brilliant work – and it’s a story that’s not uncommon. You can be proficient without being a specialist.

What caught my eye was the statement that by not expecting students to attain computer science standards of specialization in coding, programs are sending out ill-prepared students and the lack of education “has to stop. We owe the students more.” Ok, maybe so; but here’s the more important part, I think – one that has precious little to do with code if you sort through it:

Unfortunately, many programs & if not the great majority of game design programs & mislead their students into believing they will get game design jobs when they graduate, and that is simply not true.

Yes, programs do owe their students more, and it includes things like being frank, upfront, and honest when it comes to things like “potential for gainful employment.” This is a huge problem in graduate school, where there are far more hopeful PhDs than will ever be jobs. There are a lot of people who aren’t particularly upfront or honest with potential or current students (I felt very lucky to have a wonderfully supportive, yet really honest, undergraduate mentor who had a number of frank discussions with me on the state of the Ivory Tower and what I was getting myself into). How about not letting in loads more students than the job market can realistically support? Let’s be honest – even if every single program out there required every single hopeful student to attain “computer science” levels of coding ability, there still wouldn’t be enough jobs for everyone coming out of such programs (and it’s likely that a lot of talented people would fall by the wayside thanks to the addition of a certain level of specialization that’s going to be unrealistic for otherwise really talented and useful people).

Flock of Geese (Egyptian, c. 1350 BC, housed in the British Museum)

But of course, being a business these days, that would be bad for the program bottom line – and we couldn’t have that, could we? It’s a shameful problem that exists in many corners of the education sector (and makes me just as angry, if not more so, elsewhere and closer to home) and yes, we do owe the students more, including not leading them on years long wild goose chases for jobs that don’t and won’t exist, regardless of how well they do or don’t code. Maybe that ought to be a rant at GDC next year.

Back to my own corner of the Ivory Tower, there are several programs that have pretty impressive records of success (even with the lousy academic job market). I think one thing worth noting is that often, professors wind up “taking a chance” on students who may not have a “classical” background that clearly led to a given field or speciality. The equivalent, if you will, of taking a chance on the student who may not come in with computer science levels of coding but brings a lot of other things to the table – sometimes nebulous, undefinable qualities. Except these days, it seems more likely to fall in your favor than not – specialization is still expected, yes, but future employers increasingly want to know what other skills a fledgling academic is going to bring to the table. What sets you apart from all the other specialists who have the same general specialty as you. Negotiating the line between the demand to specialize and the demand to be broad and wide-ranging is one of the orders of the day.

In a glutted job market, there’s something to be said for taking a chance, both before, during, and after the education process.

The Fearless Muse

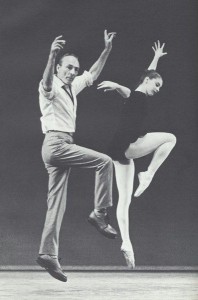

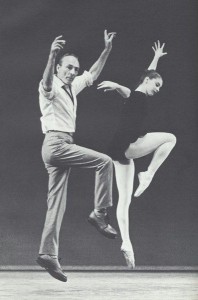

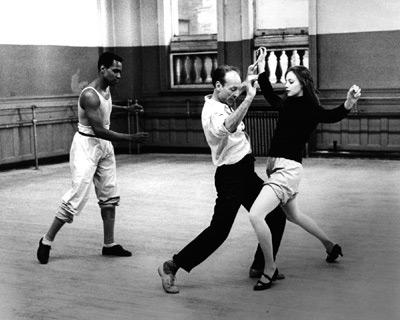

Balanchine & (a young) Farrell

While pondering these issues, I find myself thinking about George Balanchine’s last great muse, Suzanne Farrell. She’s an interesting character – one of those dancers with that nebulous je ne sais quoi (the dramatic story of her rise-fall-rise and the prominent position she occupies in the history of modern ballet doesn’t hurt). Most people agree that she wasn’t a particular star technically (e.g., she wasn’t “known” for, say, her jumps), but as the choreographer Maurice Béjart (who took her & her husband in after they were forced to leave the New York City Ballet) said about her musicality – it was as if the music came through her. That is, part of her “something” was one of the hardest things to train people at – she was just naturally gifted, and it remained one of her greatest strengths as a dancer, technique absolutely aside. Incidentally, it was also something Balanchine noticed during her audition for the School of American Ballet – and undoubtedly one reason he took a chance on the girl from Cincinnati despite her wonky left foot with a fallen arch. His gamble paid off in spades.

Anyways, Balanchine loved her for many reasons, but there are a few that get mentioned with some frequency: first, she was fearless. Unlike many ballerinas, Farrell wasn’t afraid of being off balance or falling off pointe. She wasn’t afraid of making mistakes – mistakes that sometimes led to revelations. Second (and likely connected to the first), she was willing to experiment, to try, no matter how crazy an idea may have sounded.

This was important. Because, you see, George Balanchine had never been en pointe. According to Ferrell, when they were working – creating – in the studio, Balanchine would remind her of this fact. And while working, he would ask her about things that they had never attempted before: “Is this possible? Is that possible?” (Think on that: another definition of what it means to be an “artist,” no? And a little revelatory that one of the greatest – if not the greatest – choreographers of the twentieth century had never actually practiced one half of his “instrument” at all. He didn’t always know what it was even capable of!)

“I don’t know,” she would respond, “but we can try.”

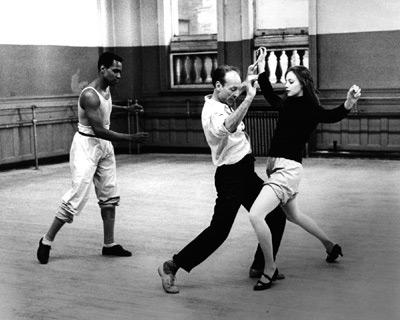

Arthur Mitchell, Balanchine & Farrell rehearsing Slaughter on Tenth Avenue

Well, 2014 was a pretty exciting year for this blog: my little post on a Chinese lianhuanhua version of Star Wars went viral (and is still garnering a pretty astonishing number of page views for a not frequently updated, kind of boring blog. It’s far surpassed even my best post at Kotaku!). I was also selected as one of Danwei’s 2014 Model Workers, which made me feel pretty good – I’m in excellent company. Similarly, I was put on the “China Twitterati 100” list of Jon Sullivan, a fellow China scholar at the University of Nottingham (admittedly, 2013 was the year with all the big guns, but considering my Twitter feed is often full of dog photos, random photos of Montana, and not much else, I was pleased nonetheless). I often feel a bit disconnected from my field, but I do try and take advantage of the Twitter ecosystem, which has proven a pretty good way to build connections with people I’d otherwise not get to interact with a whole lot (or at all).

Well, 2014 was a pretty exciting year for this blog: my little post on a Chinese lianhuanhua version of Star Wars went viral (and is still garnering a pretty astonishing number of page views for a not frequently updated, kind of boring blog. It’s far surpassed even my best post at Kotaku!). I was also selected as one of Danwei’s 2014 Model Workers, which made me feel pretty good – I’m in excellent company. Similarly, I was put on the “China Twitterati 100” list of Jon Sullivan, a fellow China scholar at the University of Nottingham (admittedly, 2013 was the year with all the big guns, but considering my Twitter feed is often full of dog photos, random photos of Montana, and not much else, I was pleased nonetheless). I often feel a bit disconnected from my field, but I do try and take advantage of the Twitter ecosystem, which has proven a pretty good way to build connections with people I’d otherwise not get to interact with a whole lot (or at all).