I try very hard (and think I largely succeed) in not being that kind of historian: you know, the one that can’t let historical “fact” go enough to enjoy what’s supposed to be entertainment. Yes, I look askance at random insertions of historical events in films or games – I haven’t (nor will I ever) played Bioshock Infinite, but my eyebrow arched when I came across references to its treatment of the “Boxer Rebellion.” If nothing else, it seemed that no one had read Joe Esherick on the Boxer Uprising (though perhaps someone on the team had, at some point – who knows). In any case, other than a slightly irritated tweet that seeing references to the “Boxer Rebellion” makes me twitchy – which it does – I don’t have much to say about even wild liberties taken with historical events. I always nurture some sort of hope that coming across scattered references will encourage at least a portion of the audience to go searching for more. After all, one of my colleagues – a wonderfully talented scholar – once admitted that his interest in China was partially ignited by playing a Romance of the Three Kingdoms themed game on SNES. Maybe one of the great China scholars of generations to come will find themselves going down the rabbit hole of late Qing history courtesy a game that largely disappointed the game criticism blogosphere? Unlikely, but stranger things have happened.

I try very hard (and think I largely succeed) in not being that kind of historian: you know, the one that can’t let historical “fact” go enough to enjoy what’s supposed to be entertainment. Yes, I look askance at random insertions of historical events in films or games – I haven’t (nor will I ever) played Bioshock Infinite, but my eyebrow arched when I came across references to its treatment of the “Boxer Rebellion.” If nothing else, it seemed that no one had read Joe Esherick on the Boxer Uprising (though perhaps someone on the team had, at some point – who knows). In any case, other than a slightly irritated tweet that seeing references to the “Boxer Rebellion” makes me twitchy – which it does – I don’t have much to say about even wild liberties taken with historical events. I always nurture some sort of hope that coming across scattered references will encourage at least a portion of the audience to go searching for more. After all, one of my colleagues – a wonderfully talented scholar – once admitted that his interest in China was partially ignited by playing a Romance of the Three Kingdoms themed game on SNES. Maybe one of the great China scholars of generations to come will find themselves going down the rabbit hole of late Qing history courtesy a game that largely disappointed the game criticism blogosphere? Unlikely, but stranger things have happened.

There are some things I am less sanguine about, however, and that includes my favorite literature. Often, seeing novels translated to the big screen is a depressing experience – how can you compress the complexities in many great works down to two hours and change? Frequently, you can’t. Rarely, I like things better on the big screen than in written form, like The Last of the Mohicans (I would much rather be forced to watch the film on loop for an eternity than have to read James Fenimore Cooper’s snoozefest one more time, great American literature or no – the Deerslayer, I might waffle on. Mohicans, certainly not). But I usually avoid cinematic versions of my favorite works, though curiosity occasionally gets the better of me.

My touchstone novel (or one of them), one I come back to over and over again, is Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. One of the first moments of serious outrage about the downfall of American culture, as viewed through popular culture, I remember having is when it showed up on Oprah’s book club. “Christ almighty,” I ranted to my mother, “it’s Tolstoy. TOLSTOY! One of the great novels of the nineteenth century! Do people really need OPRAH and a sexed up cover to tell them to read the damn book?” (probably so, is the answer). I’ve been reading it since I was 12 or 13, and I come back to it almost every year. And even when I put off the annual reading, at the very least, my very battered copy has accompanied me all over the world. That Penguin translation – inherited from my mum – is better traveled than most people. It’s an embarrassing record of nearly two decades of reading – coming face to face with what my 15 year old self thought was important enough to highlight can be positively humiliating – but an important book. I’ve read it in English and French, and I think I have a copy floating around in Chinese. I had a vague idea as an undergraduate that I might like to study Russian history, since that would mean having to learn Russian, and that would mean being able to read Tolstoy (and Pushkin and and) in their originals. Maybe I will get around to learning Russian someday, if only to commune with Anna Karenina in the original, and Sophia Tolstoy’s diaries besides.

It’s a big book. It’s a daunting book. Not only is it long (it is Tolstoy, after all), you have two relatively separate plots that come together here and there. Despite these things (or perhaps because of them), it has also proved positively irresistible for film directors. I try not to watch the cinematic versions. I have a 1967 Russian version flittering around that I’m scared to watch, although it’s been in my possession since 2006, and while I actually rather liked the 1997 version starring Sophie Marceau and Sean Bean, I first watched it under duress. I’d been studiously avoiding the 2012 film with Keira Knightley and Aaron Johnson. The initial reason for my reluctance was perhaps extremely superficial, but as it turned out, I wasn’t entirely wrong.

This is what is on the cover of my copy of Anna Karenina, the Penguin edition translated by Rosemary Edmonds:

Ivan Kramskoi’s Portrait of an Unknown Woman (1883). It’s a beautiful painting (and one with an interesting history), one that supposedly ‘inspired’ Tolstoy’s descriptions of Anna, though that’s clearly impossible based on timing. And yet, perhaps because it’s emblazoned on my trusty copy, when I imagine Anna Karenina, fictional character, I imagine something close to this unknown woman with her blue silk-edged muff.

Here is Tolstoy’s description of Anna at the important ball, one of those scenes that I come back to again and again when I think of my imaginary Anna:

Flushed, Kitty lifted her train off Krivin’s knees and, slightly giddy, looked round in search of Anna. Anna was standing in the middle of a group of ladies and gentlemen all talking together. She was not wearing lilac, the colour which Kitty was so sure she ought to have worn, but a low-necked black velvet gown which displayed her full shoulders and bosom, that seemed carved out of old ivory, and her rounded arms with their delicate tiny wrists. Her dress was richly trimmed with Venetian lace. In her black hair, which was all her own, she wore a little wreath of pansies, and there were more pansies on the black ribbon winding through the white lace at her waist. Except for the wilful little curls that always escaped at her temples and on the nape of her neck, adding to her beauty, there was nothing remarkable about her coiffure. She wore a string of pearls round her firmly-modelled neck. (93)

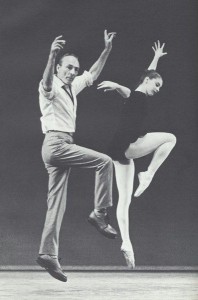

That description – of a beautiful, well-shaped woman who is clearly not waifish (I think here of Suzanne Farrell, and Arlene Croce’s comments about her 1960s, pre-Béjart shape and the “plush” and “plump quality” of her movement – for all the ranting about Balanchine’s encouragement of the anorexic dancer form, none of his great ballerinas could be remotely described as bony sticks. The young Farrell is tall and long and slender, but also round in many respects) – is one reason I managed to stay away from Joe Wright’s Anna. There was just such a fundamental disconnect between the Anna in my head and Keira Knightley that I doubted could be overcome.

That description – of a beautiful, well-shaped woman who is clearly not waifish (I think here of Suzanne Farrell, and Arlene Croce’s comments about her 1960s, pre-Béjart shape and the “plush” and “plump quality” of her movement – for all the ranting about Balanchine’s encouragement of the anorexic dancer form, none of his great ballerinas could be remotely described as bony sticks. The young Farrell is tall and long and slender, but also round in many respects) – is one reason I managed to stay away from Joe Wright’s Anna. There was just such a fundamental disconnect between the Anna in my head and Keira Knightley that I doubted could be overcome.

I hadn’t thought of the movie in ages, but one of the nice things about being back in an academic fold again is having all sorts of interesting people to talk to, including – for the first time ever in my academic career! – having people (well, one person, at least) who really have studied Russian history (formally, and they do in fact teach it – unlike my amateur interest/bathtime reading combined with the purely practical brushing up against Lenin and Stalin one must do when one studies post-1949 Chinese history) to answer all my pressing questions about late imperial Russian history (e.g., ‘When WAS the point of no return for the Romanov dynasty?’ One answer, in case you were dying to know like I was, is 1905). Anyways, we had a nice chat about Tolstoy & his wife, and Anna Karenina; I admitted I actually liked the 1997 version, but expressed skepticism on the more recent Western remake. My fellow historian hadn’t seen it.

As it happened, my mum was in town recently & in the course of sipping our wine & talking history & attempting to figure out what to do with the evening, we decided to take a chance on the most recent cinematic version of Tolstoy’s epic. And it was true: I found Keira Knightley’s mere form so antithetical to what I have imagined Anna Karenina to be like for over half my life that I never could comfortably slip into the film. It is admittedly a pretty film, and a stylized one – and Knightley’s physical presence is a nice shorthand for the bigger stylistic problems of the film, its conceits. It’s a weirdly stripped down and ahistorical portrayal of a particular period. And while it’s lush, it’s lush in a way that never quite gels.

Maybe I expect period films to be too period. But the latter half of 19th century Russia (at least among the aristocracy) seems so luxurious – so plush, like a late ’60s Farrell arabesque! – it seems a shame to dismantle it and attempt to build it back up again. The novel is so rich that it seems silly to layer on a conceit like “this is all taking place on a stage!” Yes, yes, we get it: the artificiality of society! It’s practically as if late imperial Russian society were proceeding according to a rigid set of conventions that they’re performing – like a play! (Being inspired by Orlando Figes is one thing, turning literal the idea of ‘acting’ is another: really? Did we have to be so literal?) There are clever bits here and there, but when it comes down to it, Tolstoy doesn’t need clever bits. There were striking bits of imagery – as when Anna is in the nursery of Stiva & Dolly’s house, and is seated in the children’s elegant playhouse – but flashes here and there aren’t enough. It’s a film, not a painting.

And then there are the arms. It sounds positively ridiculous – among so many other problems, décolletage and the roundness of arms are going to leap out? But when I think of the great many descriptions tucked into the novel, that description of Anna at the ball – looking even more glamorous than naïve Kitty could’ve dreamed – with her rounded arms, tiny wrists, and ‘firmly-modelled’ neck (here is where I would like to know what the Russian says, and implies: not that I distrust Edmonds, but I always wonder what I’m missing) – it’s that bit of prose I come back to (not the epigraph, and not the famous first line). Whatever the Russian says exactly, we are not dealing with a fragile, willowy beauty.

Even ignoring the fact that Wright has Anna in dress that ‘full shoulders and bosom’ would come falling out of, the horrors, and Knightley’s collarbones could cut a steak – she’s beautiful, to be sure, but Anna Karenina? This becomes more obvious when everything is in motion; she just can’t quite pull off the ever-so-slight bloom off the roseness needed; her Vronsky doesn’t help in these matters, seeming like an escapee from the Corps des Pages, not an officer. They don’t seem to inhabit the roles, instead just putting on the (somewhat off kilter and nowhere near as effective as sumptuous period costumes) clothing. The Levin and Kitty thread (lifted from Tolstoy & Sophia) – often my favorite parts of the novel – show up in random sequences here and there. The contrast is never expounded upon, and while Levin may look delightful rhythmically cutting wheat with his peasants, it’s an excuse to show rippling golden wheat – not actually develop anything.

Perhaps this is nitpicking over costuming and decisions about what part of an admittedly lengthy book a director chooses to trim. On the other hand: I think the arms are my convenient scapegoat for the fact that some versions of Anna Karenina are believable, and some are not. I suspect that even if Sophie Marceau’s arms had been a little less round, her shoulders and décolletage a little less full, she still would’ve been believable as Anna in a way Knightley just isn’t. Sean Bean is more convincing as the dashing Vronsky; the more current version looks as though he’s playing dress up out of a not terribly good costume closet (the women’s clothing – jarring as it is if you’re expecting some semblance of 19th century clothing – is at least luscious in fabric selection; the men get saddled with uniforms that look like they ran out of money before finishing them properly). She gave up everything for him? Really?

There are bones of the story that must be gotten right for everything else to work. Even seemingly minor details keep undercutting the (dare I say) authenticity of the whole project. Vronsky’s mount for the disastrous steeplechase is described in the novel as a dark bay English thoroughbred, ‘not entirely free from reproach’ but generally lovely to look upon (like Anna, then: Tolstoy never describes her as an overwhelming beauty, and she, too, would not be entirely free from reproach – but the general effect is so lovely, one hardly notices the faults). That she has been imagined in the film as a rather heavy, Iberian-looking grey horse would perhaps be forgivable if the interlude rang true (though really, how hard it is to find a bay horse); but the episode is never developed, beyond Anna’s reaction to the fall. Isn’t it more powerful if we see the parallels between the relationship that is about to overtake Vronsky and Anna and this lovely, spirited bay mare who meets a bad end? So too with the Levin-Kitty plot, left mostly untouched except for mucking up the proposal scene and random flashes here and there: doesn’t it make the titular woman’s story that much more powerful?

But perhaps my indignant response to some adaptations of Tolstoy’s wonderful novel explains my more tolerant attitude towards historical detritus sprinkled here and there. A film I love, though it’s certainly not a good film, is Le Pacte des loups (2001), which despite being a silly romp in many ways does strike some chords regarding 18th century French history. The story is preposterous, but it can feel spot on even while you’re rolling your eyes about yet another martial arts sequence. No one can recreate a period in its entirety, not even the most conscientious and obsessive historian – details are bound to be lost. We could say the same thing about recreating a novel and moving it to a new medium; what matters is not so much if every detail is correct, but if it rings true. (This isn’t to say that historians should play fast and loose with details – just that, when you’re writing a history of whatever it is you’re writing a history about, you simply can’t write everything) If I, in writing my history, haven’t managed to evoke anything about the period, if it rings false – I haven’t really done a good job of things. It may be solid history, but it’s missing something essential (of course, not all historians do work on topics or periods or themes that lend themselves to being “evocative,” and that’s fine – it’s just not the sort of history I happen to do). Perhaps this is where the most recent version of Anna Karenina fell down for me: the bones were wrong, and the silks were wrong, too.

One of the things I love most about the stories I study is that they have lived many, many lives; there are few sacred cows in the Chinese operatic tradition, and there are many examples of tinkering and adding and subtracting in the literary canon. I like it when my thoroughly Marxist intellectuals declare themselves – in highly literary Chinese – to be heirs of a great tradition, which means changing and playing and not letting it just die. It’s a testament to the resiliency of culture, and how even very old things can be reinvented over and over to remain relevant to different audiences, in different periods, in different places. I’m not adverse to beloved characters putting on new clothes, as it were – it’s fun to see, and fascinating to track. But it needs to ring true. Does Tolstoy’s novel really need flashy camera work and theatrical conceits to be made relevant? Did it really need a sexed up cover? Maybe it did – but I would like to think, if traipsing through a literary and intellectual history of socialist China has taught me anything, that literary works are remarkably resilient creatures, and many themes and stories (even old, old ones – much older than the late 19th century) don’t need much tinkering to make them resonate with the present, whenever that is. Li Huiniang wears many different clothes, but as long as her bones – the barest, stripped down essence of that Song dynasty concubine – remain solid, the adaptations work. But there are limits.

I’ve often joked – though not really joking, for if you look at my work and what I really enjoy doing and teaching, it’s really the truth – that I would’ve been happy as a clam in an EALC department as opposed to history (if we could magically subtract the considerable language chops I would’ve had to develop simply to pass my quals). I always point to the fact that Mao makes the rare appearance in my dissertation (this, despite the fact that I am a “PRC historian”), as I am much more interested in meditating on my beloved intellectuals and their literary output. But perhaps my reaction to Anna Karenina (almost all of them) illustrates that as much, if not more: I can tolerate an amazing amount of “play” with historical events, but keep your hands off my well-loved literary figures unless you’re prepared to do them justice.