I have a whole whack of backlogged posts-to-write that I haven’t gotten around to: the end of spring semester (the end of my second year as a full-fledged assistant professor!) was full and busy. Two conferences, including a trip to Canada, thoughts on teaching an experimental-for-me course, other assorted bits of my life. Frankly, as summer slides by – as it’s wont to do when you’re an academic, I was at the dentist a few weeks ago & the hygienist said to me ‘It must be so nice to have the whole summer off!’, and I could only laugh, because it’s not quite that simple – every day means it’s less likely for me to go back and write those posts, or finish the half-written ones in my queue. I may sit on quiet, cool nights and tap through my phone, looking at photographs and little snippets of video that make me smile, but I don’t really want to write about them. But a past of mine that passed into history long ago: well, that’s a little easier to write about. A little more like writing proper history.

I have a whole whack of backlogged posts-to-write that I haven’t gotten around to: the end of spring semester (the end of my second year as a full-fledged assistant professor!) was full and busy. Two conferences, including a trip to Canada, thoughts on teaching an experimental-for-me course, other assorted bits of my life. Frankly, as summer slides by – as it’s wont to do when you’re an academic, I was at the dentist a few weeks ago & the hygienist said to me ‘It must be so nice to have the whole summer off!’, and I could only laugh, because it’s not quite that simple – every day means it’s less likely for me to go back and write those posts, or finish the half-written ones in my queue. I may sit on quiet, cool nights and tap through my phone, looking at photographs and little snippets of video that make me smile, but I don’t really want to write about them. But a past of mine that passed into history long ago: well, that’s a little easier to write about. A little more like writing proper history.

I don’t pay much attention to games writing these days, and honestly haven’t for a long time – certainly not for the past year or so, since there’s been so much hateful stuff directed at people I know and respect. It’s easier – as a person no longer connected to any of that, except in the most tenuous way – to get my news in snips here and there on Twitter, on Facebook. I don’t have to watch E3 because it’s my job, so I don’t. I don’t have to pay attention to GDC or the latest press releases, so I don’t – except when it’s already been filtered through people I know and trust, who have had to go through all that shit first. The first game-related thing I’ve felt strongly enough to post about in a while was Leigh Alexander’s wonderful essay on FFVII. It was beautiful. It was worth sharing.

This past E3, the long-begged for Final Fantasy VII remake was announced. FFX was my first ‘real’ FF (I have written about that), though I had played 7 & 8 & 9 prior to that. But I had a different relationship with those games than many people my age: though I played them close-to-or-shortly-after-their-release, it was still in a sort of second hand way, not in the excitement of playing the new thing that’s just come out. I was just starting to play videogames again – and really play them in more than a ‘7 year old with a GameBoy’ way – when these games were the latest thing; I didn’t even know what a JRPG was, never mind that I loved them. But I was close enough to 7 that I can understand why people have these bigger life memories bound up in it. It is of my generation, even if it wasn’t mine. I am currently replaying FFVIII (not one of my favorites in any case, but there’s a certain amount of comfort and nostalgia in its crazy junction system and story). I remember sitting on the floor of a friend’s cramped little room that I spent a lot of hours in as a high school student, watching him play the game. I remember how that room smelled and looked and felt.

Games always conjure up memories of where I was in life when I play them. That doesn’t mean I don’t have memories, important & emotional ones, attached to other kinds of media – music is particularly evocative, of course, and I can go through my library and give you a run down of where I was in life when I first read this book or that (even academic monographs). They have feelings attached to them. I hauled a bunch of books into my office today & going through them took forever, because I kept running down the hall to say to my friend ‘Look at this little memory or that! You should read this one … Oh, look at this random piece of academic dust that is living in the pages of this book I haven’t looked at in years …’, or I just sat on the floor of my little office and paged through them silently, remembering. But those memories are never as consistently complete as game memories are.

The game related to 7 that was mine was a PSP spinoff released in 2008, Crisis Core. It’s a beautiful little game in a lot of ways. I got it not because I was so attached to 7, but because I had played 7 & was curious about how Square was going to deal with a game where you knew the outcome before you started playing. I had also lived in Taiwan between 2006 & 2007, when FFVII prequel mania was at its height – my terrible little bathroom in my terrible (but wonderful) little rooftop one room studio with no kitchen had a FFVII prequel wall hanging in it (bathroom not shown here, but you get the idea). Crisis Core is a game where the main character is one that you know is dead in 7, the game that comes after. How does a writer deal with that? Can you write a satisfying story where everyone – well, everyone that had played the main game, which is the target audience here – playing it knows the character you’re playing is going to die? They did. I cried at the end – an end I knew I was coming. Maybe that’s why I liked it: it was like writing history with a sad end, where you know things are going to end badly.

The game related to 7 that was mine was a PSP spinoff released in 2008, Crisis Core. It’s a beautiful little game in a lot of ways. I got it not because I was so attached to 7, but because I had played 7 & was curious about how Square was going to deal with a game where you knew the outcome before you started playing. I had also lived in Taiwan between 2006 & 2007, when FFVII prequel mania was at its height – my terrible little bathroom in my terrible (but wonderful) little rooftop one room studio with no kitchen had a FFVII prequel wall hanging in it (bathroom not shown here, but you get the idea). Crisis Core is a game where the main character is one that you know is dead in 7, the game that comes after. How does a writer deal with that? Can you write a satisfying story where everyone – well, everyone that had played the main game, which is the target audience here – playing it knows the character you’re playing is going to die? They did. I cried at the end – an end I knew I was coming. Maybe that’s why I liked it: it was like writing history with a sad end, where you know things are going to end badly.

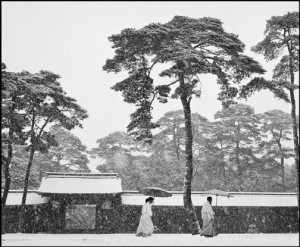

I played it on a PSP that I had bought myself on a whim the Christmas of ’07, at the end of my first quarter of grad school: I remember getting on the highway & driving down to the area with all the big box stores so I could go to GameStop. I came home with a trusty black PSP, which remained trusty and well-traveled until it was replaced with a Vita this year, long after it had become obsolete. It lives in my basement still, in its nice case, the kind that you could insert your own image into – which I carefully trimmed a photograph of the Meiji Temple in winter to fit, from my beautiful Christmas cards I used while I was in coursework. The interior simply said Peace. I still have a few in a desk drawer in my home office; I couldn’t bring myself to use all of them. I tried to find a case like that for my DS or Vita, because I just wanted to carry that beautiful image again, and I came up empty. That case (and PSP) went all over the US & to China (and various points in between), and now lives in my basement, mostly forgotten.

I played it on a PSP that I had bought myself on a whim the Christmas of ’07, at the end of my first quarter of grad school: I remember getting on the highway & driving down to the area with all the big box stores so I could go to GameStop. I came home with a trusty black PSP, which remained trusty and well-traveled until it was replaced with a Vita this year, long after it had become obsolete. It lives in my basement still, in its nice case, the kind that you could insert your own image into – which I carefully trimmed a photograph of the Meiji Temple in winter to fit, from my beautiful Christmas cards I used while I was in coursework. The interior simply said Peace. I still have a few in a desk drawer in my home office; I couldn’t bring myself to use all of them. I tried to find a case like that for my DS or Vita, because I just wanted to carry that beautiful image again, and I came up empty. That case (and PSP) went all over the US & to China (and various points in between), and now lives in my basement, mostly forgotten.

This past spring, I taught a seminar called “Games, Play & History,” which was basically a wonderful disaster. I had a lot of really wonderful students; we read some really wonderful stuff; I think I was trying to do something interesting. A lot of what I wanted to do didn’t happen, there were some unexpected bright spots that I was (delightedly) shocked by, and it was just a big learning experience in general. But while I was setting the course up in December and January, I was going through my archives and trying to find examples of good and interesting and different writing about games. An essay that kept nagging at me was one written by Leigh Alexander in 2008, about Crisis Core. I’ve read a lot (a lot) of Leigh’s writing, since my ‘career’ at Kotaku basically coincided with the early stages of her career, and while she’s written a lot of wonderful, smart stuff before and since – better stuff – this essay had stuck with me for a long time as a brilliant example of good writing on a contemporary game: striking a balance between nostalgic and insightful, personal and broad, a piece that talked about this cultural thing in her hands right now and how it connected to the past and spoke to it and was informed by it. It was, in short, a great piece of historical writing that wasn’t history. It’s what I try to do with my own academic work, I think: there is this thing I have right now in my hands that’s beautiful, and here’s why it matters beyond its immediate wonderful qualities.

I haven’t read it in years. But I remember saving a tab in my browser after it was published (where? I don’t even remember – maybe it was just on her Sexyvideogameland blog, the one that I linked to over and over when I wrote for Kotaku), and going back to look and look again, like I always do with good writing. In it, she talked about playing this game, this prequel to a game that had meant so much to her, and playing it while in the midsts of a relationship that was breaking down. And it wasn’t just that she was playing through this game where you know the main character is going to die, where the designers are deliberately making your heart stop with all these echoes of the game before, the game you are so attached to. But that original game formed the basis of that relationship that was breaking down. She wrote of this dying relationship, and silently passing the PSP between them, looking at this end-beginning – whatever one would term a prequel – that you know is going to end badly, at least for the current incarnation. And you have something here, in the right now, that is ending badly. But it’s a start, too: something new. It isn’t just the past replaying itself again and again.

I haven’t read it in years. But I remember saving a tab in my browser after it was published (where? I don’t even remember – maybe it was just on her Sexyvideogameland blog, the one that I linked to over and over when I wrote for Kotaku), and going back to look and look again, like I always do with good writing. In it, she talked about playing this game, this prequel to a game that had meant so much to her, and playing it while in the midsts of a relationship that was breaking down. And it wasn’t just that she was playing through this game where you know the main character is going to die, where the designers are deliberately making your heart stop with all these echoes of the game before, the game you are so attached to. But that original game formed the basis of that relationship that was breaking down. She wrote of this dying relationship, and silently passing the PSP between them, looking at this end-beginning – whatever one would term a prequel – that you know is going to end badly, at least for the current incarnation. And you have something here, in the right now, that is ending badly. But it’s a start, too: something new. It isn’t just the past replaying itself again and again.

It was beautiful. It was – it still is – one of the most beautiful pieces of writing on games I have ever read, partially because it was just so bloody personal and in a way that a lot of games writing, even relatively intimate stuff, just isn’t. I haven’t read it in at least six years, and I remember the way she described passing that PSP. Perhaps not in detail, but how it made her feel, because I felt it, too (and isn’t that what good writing is supposed to do?).

I don’t remember when she published the essay. Maybe it was April or May. Maybe it was June. I played through Crisis Core frantically when it first came out, in March. I galloped through it, I loved it, I finished it. I remember being glued to it, at least partially, when my boyfriend came to visit me (depressed, unhappy, freaked out, lonely me) in San Diego: it was, in many respects, easier to cling to the PSP than to him. I need to finish this. I reset it two months later, and frantically played through it again. Then took my time with the end, and maybe this is why I loved Leigh’s essay so much. I now had my own dying relationship on my hands: now I took my time in finishing it. The game, the essay, the relationship. I savored it, in a way, at the same time that it killed me to spend so much time on something where I already knew the ending. I sat in front of my shitty apartment in San Diego, on somewhat alarmingly rickety concrete steps, and smoked Camel Lights and drank Asahi, my PSP clutched in one hand. My dying relationship was different than hers, of course, but it was comforting to know that someone else had played through the same game I was now, feeling some of the same things I was feeling now.

When I pull out well loved monographs, or even novels, from my shelf, it’s hard to say that.

When I wanted to put the essay up on my course site this past January, I couldn’t find it. I wanted so badly to read it again, just for myself, even more than I wanted to be able to say to my students: This is what writing on a medium you don’t even think is very important can be. Maybe I just wanted to feel for a little bit what I had in April or May or June of 2008, when I was younger and a first year grad student and had a boyfriend I adored and still didn’t know how to handle distance. Maybe I just wanted to remember how those problems felt, the things I dealt with and survived, while I faced down new problems I don’t quite know how to manage, where I sit up late at night and whisper to myself that I don’t know if I can do this. Maybe I’m just hopeless. Maybe there is no good ending. I do know that I often find myself reading about games I loved a long, long time ago & thinking about a long, long time ago more generally (again, something that doesn’t usually happen when I read, say, book reviews of a well-loved monograph, even from years and years ago).

But it was nowhere to be found, Leigh’s essay. There is no JSTOR of old games writing.

I sheepishly sent an email to another ex-boyfriend and asked for suggestions, Where can I get this? It must exist somewhere. It has to. He gave me another email address, and said to just ask. So I did – shyly, shamefacedly. It was Leigh Alexander, after all – and who was I? Just another person cluttering up her inbox, asking for an old piece of writing she probably didn’t remember & she’d written better things since, besides. I knew that. I didn’t want her to think I thought she’d written nothing of value in the years since – not that she’d care about my opinion – it was just that this had really meant something to me.

The first time I met Leigh in person was at E3 in 2008, when we both worked for Kotaku, and as the two women on staff, had a hotel room to share. I had gotten there earlier than her, and was already set up at one of the desks when she breezed in. She was beautiful and cool and dressed so fashionably and so clearly comfortable with being Leigh Alexander. I was a shy, bumbling, nervous grad student, looking slightly ridiculous for being at a videogame event, not very comfortable with being Maggie Greene – my one photograph from that whole expedition is a selfie, showing off my E3 badge, ME with an E3 badge! How ridiculous! – and I was incredibly intimidated. We had a ‘Kotaku’ party at a bar one of the days, and I hid on the smoking porch, attached to another writer, afraid to talk to anyone. The people that did talk to me seemed shocked that I was a writer for Kotaku. I’m not sure what they were expecting, but it clearly wasn’t me. I remember towards the end of the night going up to get a drink at the bar, and seeing Leigh surrounded by people & being so comfortable. I marveled at her even as we walked back to the hotel barefooted, having taken off our pretty high heels because they were hurting our feet. I wondered if I could ever be that pretty and hip, or if I’d ever be so cool (I wasn’t, and am still not, any of those things).

I don’t think I told her then that she’d written something that I’d loved so much; in retrospect, I should have, because she probably would’ve liked to have heard that, much as I like to hear from people I know that they like my work. It means something different than random compliments, delightful as they are.

When she wrote back to me in January of this year and said that her Crisis Core essay was lost to the sands of time – worse than that, not able to be found on the internet! – it broke my heart a little bit. Oh, a piece of my past gone, I thought. And I felt bad for thinking it: she’s not writing for my pleasure. But the academic in me thought it was so sad, because – for better or for worse – all the stuff I’ve written as an academic is available, or at least findable. On the one hand, I’m glad she’s managed to make things go “poof”: it’s her writing, after all. But it’s sad to want something and be unable to find it. It’s not that we haven’t lost stuff previously. I was a Latin major in a former life, and one of my most beloved Latin teachers told us that in grad school, one of the favorite questions to sit around & discuss while tipsy was ‘If you could exchange one piece of extant writing for one piece that isn’t, what would those two be?’

My professor was talking about writers that had been lost – literally – to the sands of time, with some hope of an ancient, ragged manuscript dug up somewhere in an ancient Egyptian trash heap. I have no hope of that with a Crisis Core essay: it’s gone, just like those nights of sitting on rickety steps, chain smoking & drinking Japanese beer. Maybe that’s the wonderful and horrible thing about all these words on the internet. We talk about it as if it’s ‘simply’ disposable, but it’s ‘simply’ disposable – or becomes intangible – in the same way bits of our life do. It happened; it was; we remember; but we can’t touch it, can’t access it any more.

For now, for these little bits of digital flotsam, I just hit the ‘Paginated PDF’ button on my browser – as I did when I read Leigh’s most recent piece on FFVII – because wonderful writing might just disappear and not be hanging out in the Internet Archive for me to read, and there is no paper version. Even my own boring, run of the mill posts on Kotaku are gone, things I want now, brief records of what was important then. So I hit ‘Paginated PDF’: because you might find yourself years down the road longing to read just a certain essay, connected to nothing contemporary, since you want to remember what it felt to be like then.

It’s yet another summer of learning how to say ‘goodbye,’ something I’m not very good at, but is a constant fact of life as an academic. And I know there are all sorts of things that are happening this summer that I’m silently telling myself to remember: remember how this feels, and that, and that. Because that’s all I’ll have soon. And I tell myself to remember those things, because invariably, something – like my class, or Leigh’s recent essay, or whatever – will crop up and remind me, whether I would like to remember or not. Pass this thing back and forth, remember together. It’s sad and beautiful. It means something. There should always be something more tangible than there was this thing that made me feel once, but often, there isn’t.

There’s a beautiful poem by Mary Ursula Bethell called “Response.” She writes of letters, and minor happinesses, and the now. Also the past. The last stanza is beautiful:

But oh, we have remembering hearts,

And we say ‘How green it was in such and such an April,’

And ‘Such and such an autumn was very golden,’

And ‘Everything is for a very short time.’

It reminds me of those fleeting moments: devouring Crisis Core on my lousy San Diego steps; walking back to a hotel near the convention center in LA, barefoot because my feet hurt; walking home with a person I adore so fiercely my heart could burst; laying on my couch, half-asleep, listening to a dog dreaming loudly; all those moments from Shanghai or grad school or or or ….. I think we get accustomed to the idea that our lives online stretch on and on, last forever (after all, isn’t that what all the news articles say?). They are for such a very long time – but really, the bits that make it up can be (or are) such slippery things, and everything is for a very short time.

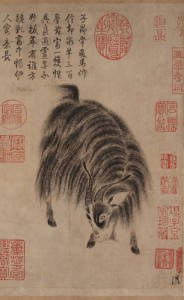

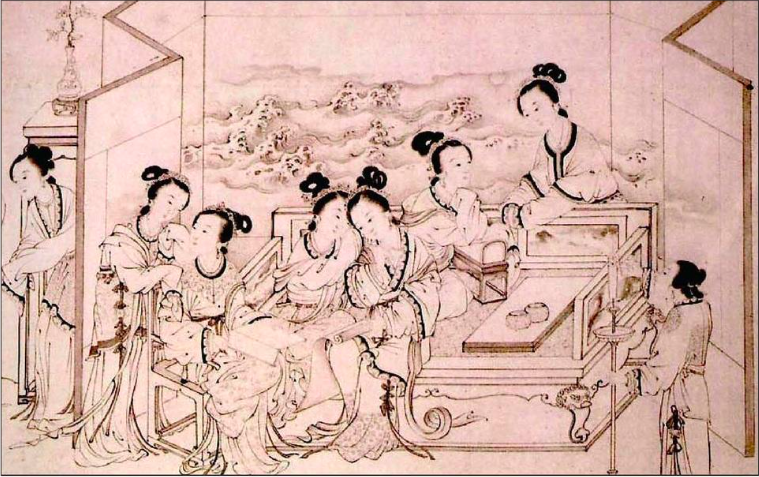

actually happen – another star serves as the “bridge”). This has, as far as I know, turned into some bizarre Valentine’s Day spin-off (at least partially), but originally, it was a celebration of women’s work (one of its alternate names is the Qiqiaojie 乞巧节, the ‘Begging for Skills Festival,’ referencing domestic skills & the practice of qiqiao 乞巧, making offerings to the Weaving Girl and holding competitions related to domestic tasks, like threading needles only by the light of the moon) & also one hoping for love or celebrating bonds. Or for missing lovers who were absent – not uncommon, at least among the poetry-writing literati, when husbands were not infrequently off on far-flung bureaucratic assignments and the like. In any case, it’s always struck me as a good deal mopier than Valentine’s Day, for the coupled and singled alike.

actually happen – another star serves as the “bridge”). This has, as far as I know, turned into some bizarre Valentine’s Day spin-off (at least partially), but originally, it was a celebration of women’s work (one of its alternate names is the Qiqiaojie 乞巧节, the ‘Begging for Skills Festival,’ referencing domestic skills & the practice of qiqiao 乞巧, making offerings to the Weaving Girl and holding competitions related to domestic tasks, like threading needles only by the light of the moon) & also one hoping for love or celebrating bonds. Or for missing lovers who were absent – not uncommon, at least among the poetry-writing literati, when husbands were not infrequently off on far-flung bureaucratic assignments and the like. In any case, it’s always struck me as a good deal mopier than Valentine’s Day, for the coupled and singled alike.

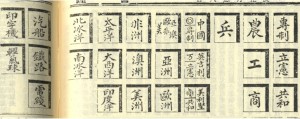

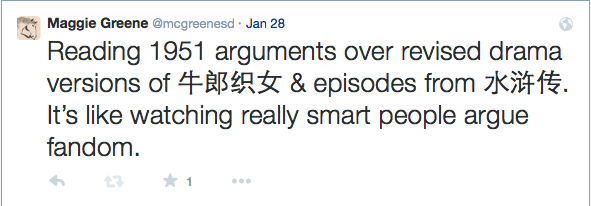

When I started looking more seriously at older parts of the historiography, I realized the field had spent some time sorting many of these people into various categories. “Establishment” intellectuals, for instance, or “revolutionary” intellectuals. These divisions can be useful, to a point; but they can also obscure a larger point, which is there was frequently a lot more similarities between these people than sorting them into different “camps” would lead you to believe. I don’t mean to imply I think there weren’t differences, or that seemingly minor differences don’t have an impact. As the political trials and travails of the 1950s and early 1960s – never mind the Cultural Revolution – indicate, there were camps, and your opinion on certain matters could have deadly consequences. But at the same time, from a distance of 70 years, there are a lot more similarities than differences. All of the people in my 1951 debate, for instance, agreed that China’s traditional culture was important and should be preserved. They disagreed on what that preservation should look like (among other things). But they agreed on one of the most important things of all: that this was worth arguing about, fighting over.

When I started looking more seriously at older parts of the historiography, I realized the field had spent some time sorting many of these people into various categories. “Establishment” intellectuals, for instance, or “revolutionary” intellectuals. These divisions can be useful, to a point; but they can also obscure a larger point, which is there was frequently a lot more similarities between these people than sorting them into different “camps” would lead you to believe. I don’t mean to imply I think there weren’t differences, or that seemingly minor differences don’t have an impact. As the political trials and travails of the 1950s and early 1960s – never mind the Cultural Revolution – indicate, there were camps, and your opinion on certain matters could have deadly consequences. But at the same time, from a distance of 70 years, there are a lot more similarities than differences. All of the people in my 1951 debate, for instance, agreed that China’s traditional culture was important and should be preserved. They disagreed on what that preservation should look like (among other things). But they agreed on one of the most important things of all: that this was worth arguing about, fighting over.