Last night, I finished a third and (hopefully – barring minor skims) final major read through/edit job on a friend’s manuscript. I’ve been a little surprised with myself: it’s been a rather emotional process, and I’m not even invested in it beyond investment in the person who’s written it. It won’t go on my CV, and it’s not like this is the project of a grad school friend, which I’ve watched from its inception. I came in at the point at which it was mostly done, marked things up, asked stupid questions, dispensed advice (as if I knew what I was talking about), wrote “clunky” a lot in the margins, and stole the techniques of my advisors, when they reminded me I was being repetitive in my prose. I frequently felt bad he was stuck with me as an editor, she of stupid questions – I could see parallels to my own academic universe, and ferried loads of books over to him (“Cite this! Look at that! This is a really important book, what do you mean you’ve never heard of it?”), but couldn’t comment much on content beyond my initial reactions (I was terribly pleased with myself upon catching a typo relating to the Crimean War: about the extent of my abilities when it comes to Russian or Ottoman history). Oh, I like this. How interesting. Reminds me of X. I’m confused. Don’t assume your readers know as much as you. I only watched the last part of the process – cleaning up a mostly final draft, being offered a contract by a press, getting edits back from the copy editor. It’s been terribly instructive, as I start plinking away at my own nascent manuscript, waiting until I’m hopefully in the same final throes.

Last night, I finished a third and (hopefully – barring minor skims) final major read through/edit job on a friend’s manuscript. I’ve been a little surprised with myself: it’s been a rather emotional process, and I’m not even invested in it beyond investment in the person who’s written it. It won’t go on my CV, and it’s not like this is the project of a grad school friend, which I’ve watched from its inception. I came in at the point at which it was mostly done, marked things up, asked stupid questions, dispensed advice (as if I knew what I was talking about), wrote “clunky” a lot in the margins, and stole the techniques of my advisors, when they reminded me I was being repetitive in my prose. I frequently felt bad he was stuck with me as an editor, she of stupid questions – I could see parallels to my own academic universe, and ferried loads of books over to him (“Cite this! Look at that! This is a really important book, what do you mean you’ve never heard of it?”), but couldn’t comment much on content beyond my initial reactions (I was terribly pleased with myself upon catching a typo relating to the Crimean War: about the extent of my abilities when it comes to Russian or Ottoman history). Oh, I like this. How interesting. Reminds me of X. I’m confused. Don’t assume your readers know as much as you. I only watched the last part of the process – cleaning up a mostly final draft, being offered a contract by a press, getting edits back from the copy editor. It’s been terribly instructive, as I start plinking away at my own nascent manuscript, waiting until I’m hopefully in the same final throes.

This process of editing – this particular round, which was on a pretty tight deadline for both of us, and the stakes seemed higher than ever because it all seems so final (I assume once this version gets shipped off, that’s more or less it: what you see is what you get in hardback) – has been difficult, and made me ponder my own work and working patterns. I don’t take criticism well, by which I mean I usually want to throw up before, during, and after reading it. It’s not that I don’t like getting feedback on my work, or that I don’t incorporate ideas (indeed, I often find it difficult not to attempt a fix on all the problems reviewers point out; I want to answer all the questions – even the big broad meandering ones, not really designed to be answered so much as point towards future research possibilities – they pose). But I often read reviews with my fingers splayed over my eyes – so I can cover them if the sinking feeling in my stomach gets too much to bear. This past year, I served as a referee for journal articles for the first time, and I tried to be so very careful in my comments and critiques. But with someone I know well (or at least, better than the anonymous-to-me author of a journal article), with my pen at the ready – and knowing I have the possibility of (as we usually do) flipping through it and boiling down my main points in person – I am much less restrained. “You’re doing it again!!” I’d write in response to some individual quirk of prose that had driven me crazy on previous drafts.

Why is this here? What does this mean? Footnotes 24 and 25 are missing. This is muddled. This should be moved to your conclusion. Move this to chapter 2. Clunky. Awkward. Rephrase. Awk. What? Weird phrase. I don’t agree with your terminology. Clarify. Confusing. I don’t understand.

Things I had perhaps thought of when reading those anonymized journal articles, but wrote carefully crafted narratives – utilizing the general formula many of us try to deploy with our students, say something good, say something critical, write how they can improve next time – to counteract; narratives that softened the blow of the criticism, of that final line saying revise and resubmit, or anything less than an enthusiastic accept for publication.

My friend called the other night, right after I’d finished reading a chapter that he’d told me he’d improved greatly after a lot of work, and the conversation seemed to go something like this:

“Hey, what’s up? What’re you into?”

“YOUR MANUSCRIPT IS AWFUL, AND I AM GOING TO EXPLAIN WHY IN EXCRUCIATING DETAIL.”

Of course, I didn’t actually say that (nor did I think it). He sounded tired, and a bit defeated, and I wondered if I should’ve just burbled pleasantries about all the things I liked at him. After we hung up, I sat and stared at my lap desk, with a manuscript – the written embodiment of years and years and years of work and sweat and tears and research and hopes and all sorts of things – spread over it, marked up with cranberry ink, and thought about all those times I had read comments on my work, from the advisors I both adored and was terrified of, from between splayed fingers.

â–

My undergrad mentor has, as I’ve explained, been a veritable font of wisdom from the first years of our acquaintance (about a decade ago, which seems crazy!) to the present. Her advice and commentary while I was in grad school always came with an extra bit of weight attached to it: we went through the same PhD program. Especially in times of crisis, it can be terribly comforting to hear from someone who’s been right where you were (literally! In the same seminar room!); someone who comes in with a certain specific perspective, not simply generalized from their experience at a different institution, with different advisors. It’s pretty rare, even in the small world subfields of disciplines can be, and it was a great comfort for me, a champion worrier.

At some point after my second year, I was grousing generally about the program and where I thought I fit into it, wondering why – despite working my tail off and making some real improvement after my first year! – it seemed like there was always something else to fix, something else to do (that I wasn’t doing), and nothing ever seemed to be good enough to garner a (desperately wished for) intellectual pat on the head. She told me something I now tell my own students: there comes a point in life where you won’t have anyone – no advisors, no fellow grads (who read your work because they have to, it’s part of seminar) – reading your stuff, giving you feedback (good and bad), and being generally invested in making you the best you can be, from the earliest days of a project. So enjoy it while it lasts; also remember that you’re going to have to rely on yourself in the future, without the protective casing of seminar. And so those years of “never being good enough” are actually good training for taking a critical look at your own work, in the absence of a room full of smart people looking at it for and with you. In academia, sure, you wind up with external reviewers, or anonymous reviewers, for this that and the other (and even the anonymous ones may, in fact, know who you are, and you may, in fact, be able to figure out who they are), and you’re generally getting feedback on your work at a certain point. But this is very different than working through the early drafts with not just luminaries in your field reading them (as your advisor – someone invested in your success), but six or seven or eight other people who are in the trenches with you.

I spent my first year and a half of grad school on heightened alert, my already defensive tendencies magnified by my fear, anxiety, and shame about being the worst grad student ever (in retrospect, I was certainly not “the worst ever,” but I was still pretty damn bad on most counts). It made the peer review section of our research seminar excruciating. I was essentially told by an advisor to knock it off; that I was smart, and probably had a future, if I stopped shooting myself in the foot by being reactive and defensive. So my second year, I tried really, really hard just to be open to those sessions, not take critiques of my work as a critique of my considerable failings as an academic and human being, and soak up all those comments. The product of that was quite good, my first foray into Li Huiniang. I still hear one of my advisors saying – in response to a first or second draft of some section – “You write like you speak – stream of consciousness!” when I’m writing. That comment didn’t fundamentally alter the way I work – my early drafts are almost always waterfalls of prose and it’s just the best and easiest way for me to work, to at least start getting ideas down – but I hear that comment when I’m editing, too. I internalized all those comments, the years of hearing feedback from known, trusted people who knew my work (and more importantly, knew me), and can generally apply it to my solitary editing activities. But I do miss those voices, and the process of sitting around our familiar table (where it seems I spent so much of my twenties; certainly spent a lot of time growing up).

â–

The process of writing a dissertation is the first exercise in that lonely world of going it (mostly) alone, albeit with the safety net of advisors and committee. But a lot of us wind up far afield from the physical location of our grad school, and it can be isolating – the three years of being a PhD candidate were pretty miserable for me, and a lot of it boiled down to being lonely and wanting people to talk to about my work on the level I was used to from coursework. I was (and am) lucky for having a friend (also far afield from her grad school & cohort) who has been the world’s best editor. I’m pretty sure she knows my work better than I do, or can at least articulate it better!

The process of writing a dissertation is the first exercise in that lonely world of going it (mostly) alone, albeit with the safety net of advisors and committee. But a lot of us wind up far afield from the physical location of our grad school, and it can be isolating – the three years of being a PhD candidate were pretty miserable for me, and a lot of it boiled down to being lonely and wanting people to talk to about my work on the level I was used to from coursework. I was (and am) lucky for having a friend (also far afield from her grad school & cohort) who has been the world’s best editor. I’m pretty sure she knows my work better than I do, or can at least articulate it better!

I went to visit her in Berlin a few summers ago, and had a week of glorious weather and very long walks (she is a marathon runner; I am chubby and out of shape, but love to walk and walk and walk, especially in beautiful places like Berlin’s Tiergarten). We did a lot of walking and a lot of talking and enjoyed each other’s company; it was also good for my work. And, in a period where I routinely went weeks without leaving the house, she was my lifeline to some semblance of sanity, and also my faithful critic and conscientious editor, albeit on Skype (the Tiergarten was preferable, but one takes what one can get). She didn’t just get a singular sentence of thanks in the dedication section of my dissertation, she got a whole paragraph on my thankfulness for her work on my behalf, and the fact she exists in my life, and those times spent in the Shanghai Municipal Archives, and that we had a really wonderful golden week of walking and talking and drinking Weissbier and eating cassis sorbet, and how much I wished we could do that more often.

â–

I talked recently with another friend about the necessity of doing things without the expectation of something in return right now (what we term “service” in the Ivory Tower). I noted I’d been thinking about it while doing this editing, and some other things this summer and over the course of this past year. I’m probably a bit too quick to say yes to things that don’t even earn me a line on my CV or on my annual review like “service,” and all those articles on the Chronicle about life as a woman in academia make me think sometimes that maybe I’m falling into that trap. But I have a hard time being extremely protective of my time – I am protective enough, but I also know myself well enough at this point to know that locking myself away with no distractions generally leaves me staring at blank walls, blank Word docs – in short, not being particularly productive despite shuffling everything off my plate. It seems that people are constantly telling me to shuffle more and more off, to focus, focus, focus!, and all I can think is how boring that would be, and how lonely, and I already went through that with the dissertation, and I think another round of that misery might well kill me.

And really, when I total up the time I spend on those minor things – saying to a colleague, “Yes, I’ll help you set up your website,” for instance – or even more major things, like “Yes, I’ll read your manuscript,” they don’t really take up that much time. I’ve poured a lot of effort into this final draft because I care about the person who wrote it, and want the final work to be the best it can be for his sake; but I’ve also dedicated so much time to it because it’s summer, and I’m flitting from task to task in any case, and I can afford to pour six hours a day into combing through prose. There’s a fixed deadline in sight; this won’t go on forever; and it would be horrendously selfish of me to say “Do it yourself.”

I don’t think saying “Yes, I’ll read your manuscript on a subject I know nothing about” last November was a sign of being saddled with or internalizing certain expectations that come with being a female academic (that we’ll be nurturing and helpful, for instance); it was more that I understand the value of having someone read your work and give you feedback. It was a kind thing to do, and I suppose it was a generous thing to do; but I’ve benefited from having people do the same for me, and it didn’t really occur to me to say no. I generally assume people will approach my requests in something of the same manner. And if they don’t – well, I know to dial back the amount of effort I’m willing to put in for them.

And I think now that even the cranky marginalia is a generous thing, possibly the most generous thing: I realize now, in a way that I didn’t then, that those years of critique, the underlined sections letting me know just how clunky my prose was, the skeptical looks when I was explaining some half-baked thesis, came from a place of really caring about my work. And in some respects, represented a certain amount of belief in my talent and potential: the path of least resistance when editing is the intellectual pat on the head, the “Yes, yes, it’s fine, fine.” But that, of course, is not what leads to any measurable improvement. And I’m very grateful for all the people over the years who have read my work with a critical eye; I hear their comments in my head now, and it makes my work – done now in a much more independent manner – better.

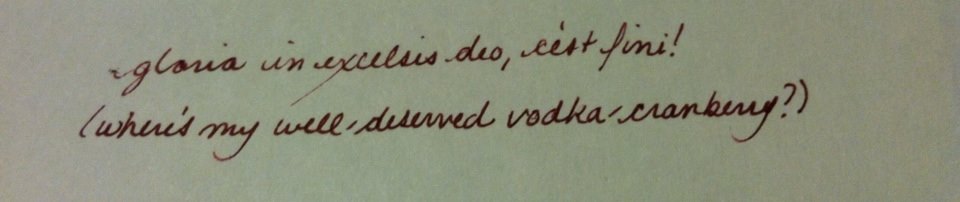

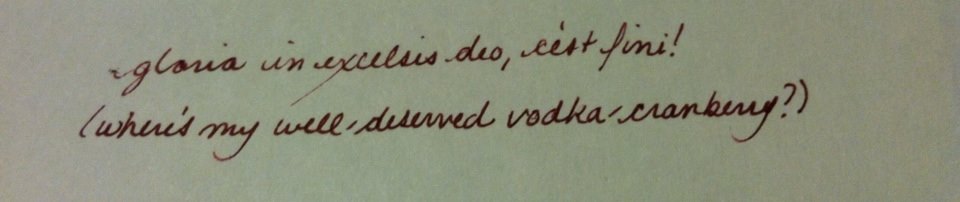

When I hit the last page of the conclusion, I wrote, feeling plucky and pleased with myself for having gotten through the whole thing in pretty good time:

What I maybe should’ve written was what a good book it is (despite my exasperated comments), and how I think it’s an important book, and how I hope people outside of his specialties will read it, and that I think he’s a brilliant person doing pretty singular stuff. But though all of that is true, I think my cranky marginalia is probably a better mark of the esteem in which I hold it: it’s more effort than the platitudes, true as they are.

It took me a long time to learn that. I was tickled when he told me, working on a previous draft, that he could anticipate my response: just like I can hear my advisors and professors and fellow grad students and Amanda! The fact that I carry those voices with me, all those comments written over the years, means that people cared enough about me and my work to want to make it better. It was a gift of a very particular sort, and perhaps not as immediately satisfying as concrete affirmations of my value, but irreplaceable: one of relative self-sufficiency in taking my work and making it the best it can be. Working in isolation, yet not. It’s one I’m immensely grateful for, and one I try – and largely succeed, I hope – to pay forward.

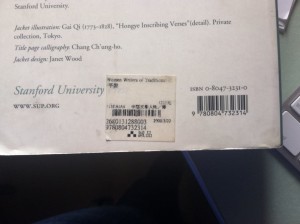

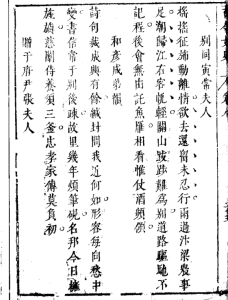

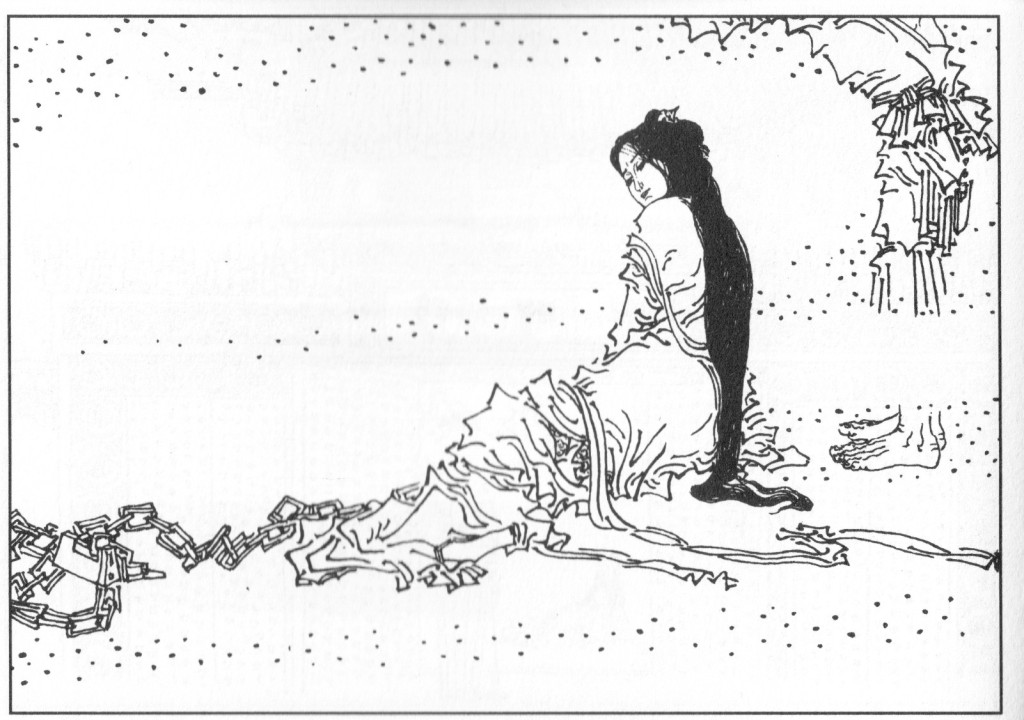

I bought a wondrous anthology while living in Taiwan, back in 2006; it’s called Women Writers of Traditional China (I’ve written about it before), and at the time, it seemed like it cost a bloody fortune (little did I know how quickly my spending on books would accelerate in the years after that!). I teach with it now, and while I can’t say my students always love the same things I do, nor can I say I do a great job teaching with it (yet)1, I’ve had enough good responses to think that I should keep trying to teach with it. I nearly fell over when a student – who had been in my lower division course & read some poetry of Qiu Jin 秋瑾 there – excitedly told a classmate in my spring semester gender course about that badass revolutionary woman poet, and seemed genuinely pleased when I said we’d be reading her again (as I’ve noted before, I actually have a deeper appreciation for her friend Xu Zihua å¾è‡ªè¯, but I get the appeal of Qiu Jin, in all her beheaded revolutionary glory). In any case, it was really important for me at the time – something I enjoyed spending a little time with every day, a bit of an inspiration. My Chinese was awful, but someday I’d be able to read all that (and, with some exceptions, I can, though I’m woefully out of shape when it comes to producing elegant translations – one reason I often use examples from the anthology when writing here).

I bought a wondrous anthology while living in Taiwan, back in 2006; it’s called Women Writers of Traditional China (I’ve written about it before), and at the time, it seemed like it cost a bloody fortune (little did I know how quickly my spending on books would accelerate in the years after that!). I teach with it now, and while I can’t say my students always love the same things I do, nor can I say I do a great job teaching with it (yet)1, I’ve had enough good responses to think that I should keep trying to teach with it. I nearly fell over when a student – who had been in my lower division course & read some poetry of Qiu Jin 秋瑾 there – excitedly told a classmate in my spring semester gender course about that badass revolutionary woman poet, and seemed genuinely pleased when I said we’d be reading her again (as I’ve noted before, I actually have a deeper appreciation for her friend Xu Zihua å¾è‡ªè¯, but I get the appeal of Qiu Jin, in all her beheaded revolutionary glory). In any case, it was really important for me at the time – something I enjoyed spending a little time with every day, a bit of an inspiration. My Chinese was awful, but someday I’d be able to read all that (and, with some exceptions, I can, though I’m woefully out of shape when it comes to producing elegant translations – one reason I often use examples from the anthology when writing here). When I was 23, I sat in my favorite restaurant in Taipei at the end of a massive dinner with friends who were leaving, and having consumed a lot of Asahi and a lot of lamb chops and a lot of other delicious things, we sat over our beers and the weight of the evening kind of settled in. We smoked our cigarettes and drank our Asahi and at some point I burst into tears, because I already missed them. I quoted a bit of Chen Deyi 陳德懿 (though my Chinese was not yet good enough to do it in Chinese): “Not knowing when we shall meet again, let’s write letters./Looking at each other, we only pick up cup after cup of wine”2 åŽä¼šæ— 由托鱼é›ã€‚相看惟ä¼é…’频倾。 If I had known that goodbyes were going to become such a standard part of life, that writing letters – well, long novellas of emails, in my case – was going to be how I maintained connections to people I loved most, I don’t know if I would’ve gone to grad school. I wonder sometimes if I’m just shy enough – and get just attached enough, just quickly enough – that this was a really unsuitable career path for me. On the other hand, it is a great joy, having all those people in my life who I wouldn’t have met otherwise.

When I was 23, I sat in my favorite restaurant in Taipei at the end of a massive dinner with friends who were leaving, and having consumed a lot of Asahi and a lot of lamb chops and a lot of other delicious things, we sat over our beers and the weight of the evening kind of settled in. We smoked our cigarettes and drank our Asahi and at some point I burst into tears, because I already missed them. I quoted a bit of Chen Deyi 陳德懿 (though my Chinese was not yet good enough to do it in Chinese): “Not knowing when we shall meet again, let’s write letters./Looking at each other, we only pick up cup after cup of wine”2 åŽä¼šæ— 由托鱼é›ã€‚相看惟ä¼é…’频倾。 If I had known that goodbyes were going to become such a standard part of life, that writing letters – well, long novellas of emails, in my case – was going to be how I maintained connections to people I loved most, I don’t know if I would’ve gone to grad school. I wonder sometimes if I’m just shy enough – and get just attached enough, just quickly enough – that this was a really unsuitable career path for me. On the other hand, it is a great joy, having all those people in my life who I wouldn’t have met otherwise.

Well, the

Well, the

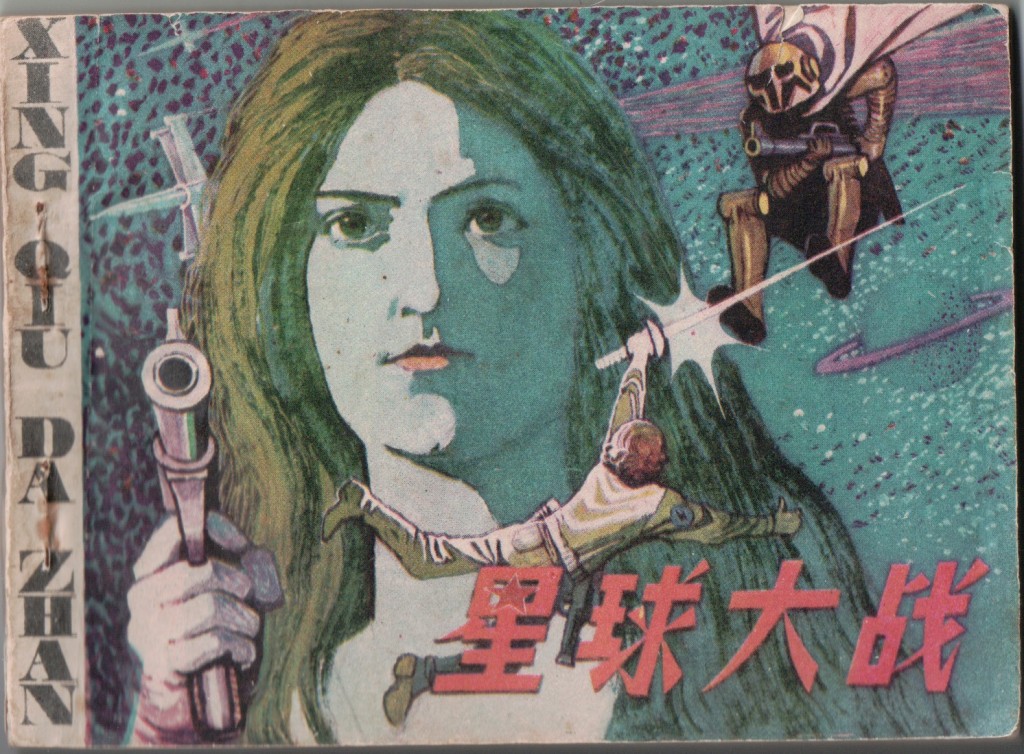

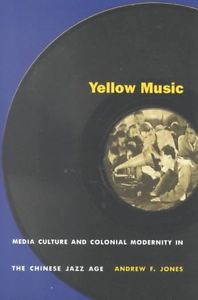

Games are interesting to plonk down in this context, because we treat them very differently than, say, Chinese opera: they’re global in a way a lot of other cultural products aren’t, almost from their inception. In Yellow Music, Andrew Jones discusses the circulation of jazz (and technology) in a way that’s resonated strongly with me over the years (in a monograph that has the hands-down best conceptual use of “colonial modernity” I’ve ever come across). He notes that one African- American’s account of the Chinese jazz age of 1930’s Shanghai “alerts us to the folly of trying to understand Chinese jazz as an example of Western influence on Chinese musical forms. Nor can the ‘Chinese’ in ‘Chinese jazz’ be relegated to the realm of the merely adjectival ….” He further notes that we must “look at the ways in which both (and indeed all) parties have been and continue to be inextricably bound up in a larger and infinitely more complex process.” While we sometimes append some sort of national marker to games (the ‘Japanese’ in JRPGs springs to mind here), we frequently don’t – often because national origins are obscured through translation and localization, and a rather interesting process of naturalization.

Games are interesting to plonk down in this context, because we treat them very differently than, say, Chinese opera: they’re global in a way a lot of other cultural products aren’t, almost from their inception. In Yellow Music, Andrew Jones discusses the circulation of jazz (and technology) in a way that’s resonated strongly with me over the years (in a monograph that has the hands-down best conceptual use of “colonial modernity” I’ve ever come across). He notes that one African- American’s account of the Chinese jazz age of 1930’s Shanghai “alerts us to the folly of trying to understand Chinese jazz as an example of Western influence on Chinese musical forms. Nor can the ‘Chinese’ in ‘Chinese jazz’ be relegated to the realm of the merely adjectival ….” He further notes that we must “look at the ways in which both (and indeed all) parties have been and continue to be inextricably bound up in a larger and infinitely more complex process.” While we sometimes append some sort of national marker to games (the ‘Japanese’ in JRPGs springs to mind here), we frequently don’t – often because national origins are obscured through translation and localization, and a rather interesting process of naturalization.