I had a long post regarding the cancellation of the fiscal year 2011 Fulbright-Hays competition written up. It – mostly a ‘What winning the Fulbright-Hays has meant to me’ post – depressed me too much, so I’ve deleted most of it. I was recently told I was being “practically nihilistic” about the future of America and American academia, and this is one reason why. Even though I have won a Fulbright-Hays and have that money safely in the bank (literally and figuratively), the news was devastating for what it signals about our priorities and the future. I hope, though, that this tremendous shock to those of us in fields that rely on the Hays and similar grants to get our work done will mean a more positive, active direction for the future. I’d like to feel less nihilistic, and a lot of us would like for our future to look a little brighter – and maybe we can make it so.

I had a long post regarding the cancellation of the fiscal year 2011 Fulbright-Hays competition written up. It – mostly a ‘What winning the Fulbright-Hays has meant to me’ post – depressed me too much, so I’ve deleted most of it. I was recently told I was being “practically nihilistic” about the future of America and American academia, and this is one reason why. Even though I have won a Fulbright-Hays and have that money safely in the bank (literally and figuratively), the news was devastating for what it signals about our priorities and the future. I hope, though, that this tremendous shock to those of us in fields that rely on the Hays and similar grants to get our work done will mean a more positive, active direction for the future. I’d like to feel less nihilistic, and a lot of us would like for our future to look a little brighter – and maybe we can make it so.

A few links to relevant posts on the issue (also see the Facebook group that has sprung up):

The official cancellation notice (US Department of Education)

Acknowledging the Value of Fulbright-Hays Research Grants (The China Beat)

Has the Fulbright-Hays Cancellation Affected You? (China Dissertation Reviews)

Killing Fulbright-Hays (Sean’s Russia Blog)

The Fulbright-Hays is Cancelled. Do Something (Christine & Rokas)

What follows below are a few notes on what this whole disaster has stirred up in my mind, as a recipient of a FY2010 Fulbright-Hays (that would be last year’s competition).

For many of us, tucked alongside the leap from “PhD student” to “PhD candidate,” the crafting of dissertation prospectus, and putting committees together is the scramble to secure funding for our fieldwork abroad. In the case of doing research in China, we have to put in serious time: even accessing archives can be a true test of patience, and one that requires cooling one’s heels while trying to rustle up letters and introductions from the right people. It’s possible to fund such ventures on your own, of course, but since a life in academia is generally a losing proposition financially, it doesn’t make much sense to go into debt over it. And it’s difficult to acquire a nice big nest of savings on a teaching assistantship – or it is at many schools in many areas. So we write, edit, rewrite, edit some more, solicit letters of recommendation, order transcripts, write, and edit in the hopes that one of those nebulous “committees” will read our applications and deem our projects worthy of funding.

It’s a crapshoot at the best of times. What do the committees want? What’s going to catch their eye? Writing a proposal is partially a game – a game of showmanship. Knowing what to say, how to say it, and how to frame your proposal to generate the maximum appeal is a fine art. I was lucky enough to have professors who turned a critical and knowledgable eye towards my essays and CV and helped me put together an application that was, in the end, successful. It was step one in really learning how to play the funding game. A successful application meant that I could move to China for a year and research my dissertation – a crucial, unavoidable part of writing a dissertation on modern Chinese history, funding or no. It’s a step I would have had to take at some point, but winning a Hays meant that I didn’t have to dip into my own (non-existant) funds to do so. It also meant I got to stay “on track” with my graduate career, and didn’t have to stress about how I was going to put food on the table and work on my dissertation.

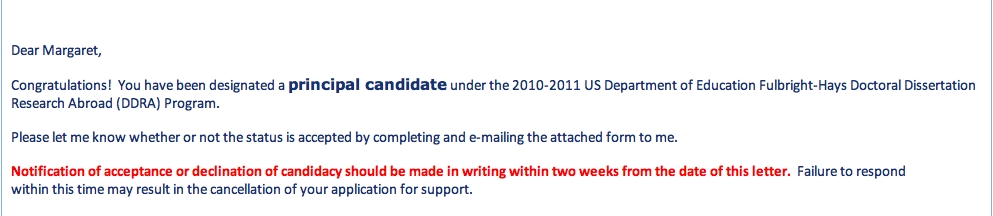

Unfortunately for this year’s applicants, the rules of the game were changed on them last minute. Actually, the rules weren’t changed: the game was just axed entirely. The Fulbright-Hays program (which includes more than just the Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad (DDRA) component) was totally defunded at the last minute. Well – not even last minute. Last year, we were notified in late April of our application status. This year, after weeks of being told that decisions were coming, the competition was cancelled in late May.

On the one hand, we’re used to bad news in higher education. On the other, losing the Fulbright-Hays – for only a year, or even more terrible to contemplate, forever – is more than just bad news. Maura Cunningham at the China Beat succinctly summed up my feelings on why this is really, really bad news:

What concerns me most about the cancellation of the Fulbright-Hays isn’t necessarily its immediate effects on my colleagues and myself, though those aren’t insignificant. Rather, it worries me—even frightens me—that with this action the U.S. government is signaling its lack of commitment to education and forging bonds with communities abroad. Programs like the Fulbright-Hays grants aren’t just about supporting individual scholars; they have a larger mission of promoting work that collectively helps all of us contextualize the world we live in and recognize how it has come to look the way it does. By not providing the funding necessary to support this year’s crop of applicants, the government is implying that such work isn’t important, that we can exist in a global community but don’t need to understand it.

I have a shelf full of books whose acknowledgements indicate that American leaders grasped the significance of this mission in the past. I am now concerned, however, that few are willing to continue it into the future, and this loss, surely, will be to the detriment of all—not just graduate students.

An easy target for those of us in area studies is area studies itself. Lots of books exist on the subject; certainly we could spend all day talking about Cold War formations of knowledge and power structures. There’s no doubt that there were and are problems with that structure, and I appreciate the fact that many dream of alternatives. But there are legacies that aren’t so negative – such as the Fulbright grants. In an era when universities are more interested in making money than promoting scholarship and education, there were (and are) funding sources that give money simply for the purpose of advancing knowledge and broadening our view of the world. And as huge a difference as the Fulbright-Hays has made for generations of graduate students, its funding was really a drop in the bucket compared to other national issues – the FY2010 competition clocked in at under $6 million, funding nearly 150 projects on incredibly diverse topics.

One of my favorite essays, and a particularly terrifying one, comes via the edited volume Learning Places: The Afterlives of Area Studies (Duke, 2002). I first read Masao Miyoshi’s “Ivory Tower in Escrow” towards the end of my first year, while in my Japanese history course at UC San Diego (the article was originally published two years prior in boundary 2, the version I quote from below). Miyoshi describes the “ivory tower” in the United States as increasingly bound to corporate R&D interests (and the increasing irrelevance of the humanities to that project), and considers the role academics in the humanities have played in allowing the humanities to become increasingly irrelevant. It is startling – saddening – that Miyoshi’s article was published 11 years ago. How far we have come (?). What would this essay read like today? Yet it seems more important than ever to take heed of his warning, issued over a decade ago:

It is pathetic to have to witness some of those who posed as faculty rebels only a few years ago now sheepishly talking about the wisdom of ingratiating the administration—as if such demeaning mendacity could veer the indomitable march of academic corporatism by even an inch. To all but those inside, much of humanities research may well look insubstantial, precious, and irrelevant, if not useless, harmless, and humorless. Worse than the fetishism of irony, paradox, and complexity a half century ago, the cant of hybridity, nuance, and diversity now pervades the humanities faculty. Thus they are thoroughly disabled to take up the task of opposition, resistance, and confrontation, and are numbed into retreat and withdrawal as ‘‘negative intellectuals” —precisely as did the older triad of new criticism. If Atkinson and many other administrators neglect to think seriously about the humanities in the corporatized universities, the fault may not be entirely theirs.

If all this is a caricature, which it is, it must nevertheless be a familiar one to most in the humanities now. It is indeed a bleak picture. I submit, however, that such demoralization and fragmentation, such loss of direction and purpose, are the cause and effect of the stunning silence, the fearful disengagement, in the face of the radical corporatization that higher education is undergoing at this time. (48)

I don’t know how world shaking my Fulbright-Hays will be. I don’t know what my future career looks like. But I know that whatever comes in the future, I don’t want it (or me!) to be labeled “insubstantial, precious, and irrelevant” or “useless, harmless, and humorless.” I was fortunate enough to win a Fulbright-Hays, an opportunity that this year’s applicants won’t get, and future graduate students may not get, either. It’s symptomatic of a very diseased whole, and I sincerely hope that the sudden shock of this cancellation means that we will take a good hard look at ourselves and our institutions. I hope that we’ll rise to the challenge that Miyoshi set out eleven years ago. The time for silence has long passed.

I hope that this year is a fluke (though I fear otherwise), and that life-changing emails like the one I got will start flowing again soon. But it’s not going to happen by keeping quiet and allowing the status quo to continue. We have been too silent, allowed ourselves to be too fragmented, and lacking in direction. This is yet another wakeup call for all of us – maybe we’ll listen this time.