Fair warning: this is rough and addled; I’m in a particularly manic phase of writing/research of my dissertation, which has spilled over into all sorts of areas of my life. But it usually manifests in the desire to write something – anything – other than my dissertation, and read something – anything – other than my sources, leading to half-baked and somewhat frantic bits and pieces of writing spilling out at inopportune moments. This was originally supposed to be more on the concept of ‘female role models,’ but it wound up being more a meditation on what we find worthy of attention and valorization when it comes to female characters or historical personages.

For my nineteenth birthday, I bought myself a PlayStation 2 and a copy of Final Fantasy X. It was something of an impulse purchase, but I passed a nice week afterwards holed up on my first real gaming binge. While I’d played through the Final Fantasy offerings for PS1, FFX was the first of the series to really catch me, and it’s part of the reason I’m generally playing some JRPG or another, or nothing at all.

For my nineteenth birthday, I bought myself a PlayStation 2 and a copy of Final Fantasy X. It was something of an impulse purchase, but I passed a nice week afterwards holed up on my first real gaming binge. While I’d played through the Final Fantasy offerings for PS1, FFX was the first of the series to really catch me, and it’s part of the reason I’m generally playing some JRPG or another, or nothing at all.

Ten years after the fact, I still have a great affection for the world and characters of FFX (if not always the voice acting); I’ve even gotten over my embarrassment at admitting that (a) I really do love FFX when talking to more old-school FF fans and (b) I cried at the end, and was delighted to have what amounted to an official fanfiction-esque sequel. It’s a game space I feel very comfortable in – appropriate, I think, for a game that marked the real start of my adult interest in games.

It may seem to be a bit of an odd game to select when talking about ‘female role models.’ There’s no one who comes out swinging a sword bigger than she is, or really turns expected JRPG roles on their head. Yuna is delicate and feminine (and a white mage, natch), Lulu is one sharp gasp away from heaving right out of her corset, and Rikku is young, lithe, and perky. I liked Lulu right off the bat, her snark and cynicism appealing to my own snarky, cynical self. But in the years since my first play through, I’ve come to appreciate Yuna more and more. I don’t know that I would describe her as a ‘role model’ precisely, but I like her. While she’s generally a pretty well-liked character, I used to be baffled by the occasional criticism I came across: ‘She’s naïve! She’s weak! She’s wishy-washy! She needs a man to give her life direction! She’s so damn nice! Her voice acting sucks! I hate female characters like that!’ Even if you don’t hate characters like her, she’s not exactly the first example trotted out when talking about ‘female characters we need more of in games.’ And yet …

… and yet. There’s a quiet moral strength about her, steel wrapped in a pretty obi. It’s a strength that’s compelling to me, and has only become more so in the years since I first played the game. In my head, the ‘Yuna’ archetype runs together with a type of virtuous woman often celebrated in imperial China. I find many of them quite inspiring – for their talent, for their bravery, for their ability to get things done in adverse circumstances. They aren’t swashbuckling heroines, but there is something about them. In the same way, I find there’s something about Yuna – her sense of purpose (no man necessary), her bravery (she is not a damsel in distress), her quiet, constant belief in herself and what she’s doing. Perhaps it’s that there sometimes seems to be a small gap between a somewhat mild temperament and less bombastic forms of heroism, and women as ineffective sweetness and light – there’s something a little uncomfortable about championing this particular form of heroism. Does it hew too closely to a narrative of what women are simply expected to be? Does it simply not push the envelope enough?

(More Ancient) Iron Girls

One of the great challenges of teaching women’s history in China is walking a fine line between valorizing the agency women had/made for themselves and being realistic about social, cultural, and political oppression. I have shelves full of books that swing from one extreme to the other – there’s the 1970s feminist scholarship that decried the fate of generations of Chinese women who were utterly oppressed by the patriarchy and Confucian order. In reaction to that, we have more contemporary works that highlight the experiences of small numbers of women to show that women weren’t simply locked in the inner quarters, bound footed and pregnant. The former is hideously negative, flattening the lived experiences of women and their own voices, the latter a bit too rosy at times. When I pull out the writings of women in my own teaching, I usually tell my students that while we can’t and shouldn’t ignore the very real negatives that women had to contend with, I want to at least give them a glimpse of the inner lives of some of these otherwise faceless women. Many of them weren’t simply vessels to carry on the family line; they did have rich intellectual and interior lives, interests, friends; they were loved. They made spaces for themselves, and they were not simply blank witnesses.

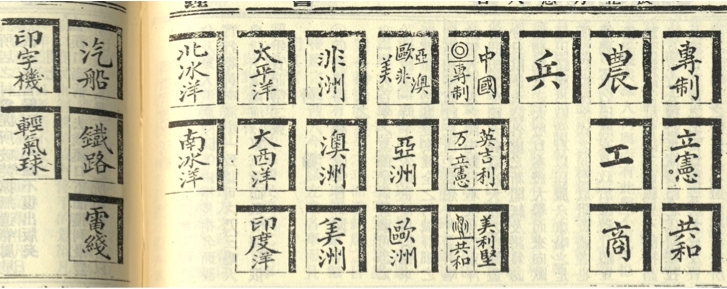

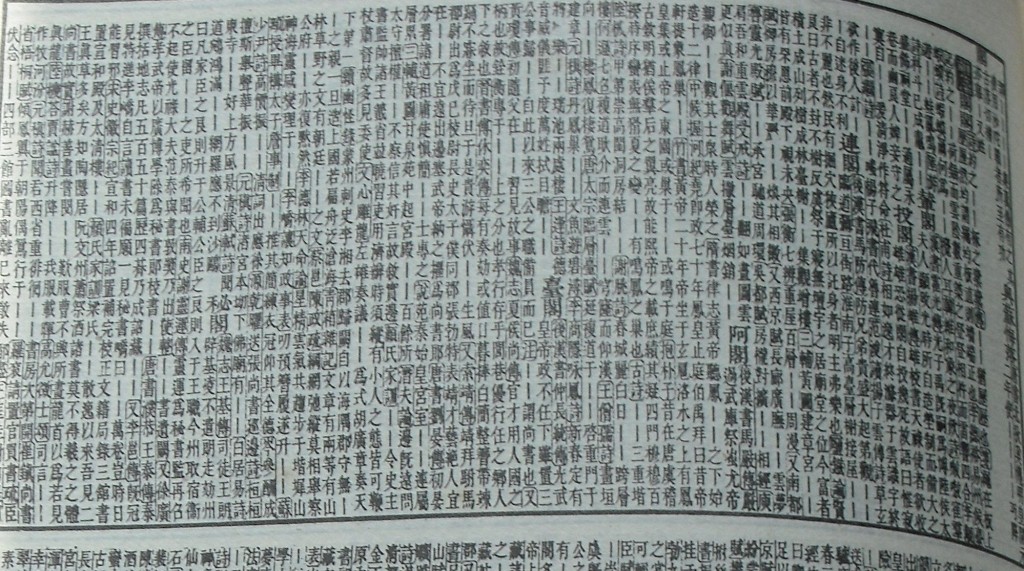

One of the most treasured, battered volumes in my entire library is Women Writers of Traditional China (it’s such a favorite, I’ve made a habit of gifting it to people for whom it seems even vaguely appropriate), a spectacular anthology that pulled together some of the very best translators to cover two thousand years of women’s writings, primarily poetry. I like introducing people to these amazing women, who run the gamut from pampered daughters of elite literati families to courtesans, but the things that make them such exemplars can be somewhat unsatisfying for modern sensibilities, I think. These are generally not Mulans come to life: they aren’t marching off to war, they’re not fooling the patriarchy by passing as men, they don’t attain glory in particularly manly ways (at least, not to Western eyes: however, there is something to be said for the fame many reached in manly intellectual pursuits). It can be difficult to make these stories sing for students – they often see these women as victims at worst, at best rather dull examples of ‘good women.’ Certainly they don’t seem to be heroes.

I think the discomfort stems in part from the fact that these women have little agency in the ways that we would like. To be sure, there were plenty of constraints in the often repressive Confucian moral code. It should also be noted that their biographies hew closely to the classic tales of virtuous and moral women, which have their own patterns and expected outcomes. And certainly, there is often a lament in the biographies – sometimes quite explicitly – that ‘if only she had been a man!’ There are tales of badly arranged marriages and horrible stepmothers; a not insignificant number of the great poets were themselves courtesans.

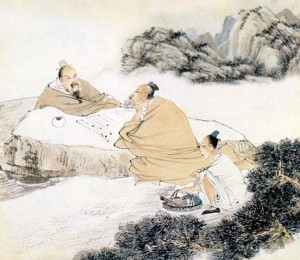

Qiu Jin, dressed in a Japanese style & as a man

Red clouds closing in on all sides as evening sorrow rises;

A lonely boat in a river full of wind and snow.

How I can I bear to walk the road to Shanyin today

Where no one but me comes to bury Autumn?1

I would be curled into a shell-shocked ball, and don’t think I would deal nearly so well with making burial arrangements for a well-loved person who was now in two pieces instead of one. Especially when such action would encourage more attention from the authorities who had just arrested and beheaded said friend.

I don’t mean to imply that it’s only these types of ‘quiet’ strength that are worthy of attention, just that perhaps we don’t give it as much attention as it deserves. It’s something that is harder to valorize than the more obviously ‘heroic’ qualities. Qiu Jin is a clear hero, and she hits some of those points we like: she shunned the expected female roles of her time (leaving her husband and children to head to Japan), she embraced the idea of revolutionary violence, she was photographed with weaponry. Delicate Chinese flower she was not, despite having bound feet. But there is heroism in Xu Zihua’s story: it is not bombastic, and it doesn’t involve assassination plots, but it speaks to a person who willingly bore a tremendous responsibility in a volatile time.

Of course, there’s a problem when it comes to talking about videogame characters and their sense of self – unlike the historical women, who were writing their own version of their life (real or imagined), Yuna is scripted, largely (entirely?) by men, and while she’s a hugely important character in the game, she’s not the main character. She is not writing her story. But she’s not simply a cookie cutter female-in-a-game, though, just as these women poets I so adore are not simply cookie cutter images of what people imagine ‘a traditional Chinese woman’ to be.

Are they women to be emulated? Are they role models? There are few characters or actual people I’d point to and say ‘We should all desire to be like that!’ Virtues of Ming-Qing China (to say nothing of fictional worlds) are not always virtues in modern society, and some of them can seem downright horrifying. The faithful maiden cult, a complement to the cult of the chaste widow (i.e., women who did not remarry after the death of a husband), is one of those – who in their right mind would point to young women committing suicide after the death of a fiancé as a model to emulate? On the other hand, there is the shape of many of these stories and biographies. Would that I could write like many of those poets, or have such an intellectual command of a vast literature and history. Would that I were able to stick closely to my own sense of purpose, and see things through to completion with a clear mind. Would that I could take the vicissitudes of life in stride without balancing on the edge of a nervous breakdown. Would that I were such a loyal friend.

The Far Horizon Road

I love the candy-colored world of Spira; grey faux-medieval cities rarely do much for me (I love wandering them in real life, not so much in a game). My ideal landscape can be summed up by another Chinese poet, Zhang Yaotiao å¼ çªˆçª•: 万里秋光碧, ‘boundless emerald-hued autumn light,’ or more poetically, ‘miles and/miles of autumn/light – sapphire/turquoise,/jade.’2 I like the relatively cheerful attitude of many of the characters – perhaps the brooding lead, à la Cloud or Squall, reminds me a bit too much of myself, and it’s not as comfortable an experience to slip into. But I also like the fact there’s a bit of melancholy that pervades much of the game. It reminds me of my favorite Chinese poems: beautiful, lush language that is by turns happy and sad. It’s wonderfully bittersweet in a way. I have the same feeling traipsing through the world of FFX: I know how things are going to end, I know that it’s going to make me sad, and even so, there’s something wonderful about everything leading up to that.

Niether Yuna, nor all my beloved poets of centuries past, are particularly likely candidates for role modelhood. They’re not particularly badass women, at least in the ways that we usually talk about it, c. 2013. They often conform a little too closely to the roles we collectively expect women to fall into (and that we fight against): quiet, cheerful, willing to subsume personal happiness for the good of the whole, naïve. But I wonder sometimes if it’s not like focusing on the bound foot to the exclusion of the entire woman. Just as the act of binding their feet did not cripple their minds, surely having what some might define as classically ‘feminine’ traits does not mean they’re simply yet another version of the virtuous, silent, ineffective, inactive woman? Fictional characters can be rather difficult – most of us know we need to take historical people on their own terms. Paraphrasing from an excellent scholar, getting on a moral high horse about foot binding, for instance, does precious little for us; trying to understand it in context, getting past that first ‘Ohmygod, how disgusting/barbaric/appalling’ reaction, is much more valuable. But what to do with fictional women? Whose terms should we take them on? Are we reinforcing the more overtly negative portrayals of women if we embrace less overtly heroic portrayals?

There’s a lot of longing for a someday that seems forever out of reach in both classical Chinese poetry and videogame criticism. Perhaps that’s just a human impulse when presented with realities that are not currently to our liking.

By the azure edge of the evening clouds – do you know where it is?

Beyond the four mountains – perhaps you dwell in the mountains there.

One sheet of crimson clouds comes, cutting across the bamboo,

Two lines of white birds go, parting the smoke.

I stretch my eyes: my heart is tangled in ten thousand threads.

Leaning against the wall, I softly chant “Jian jia.”

My longing makes me dream of the far horizon,

Though I still don’t know the way on the far horizon road.3